Property, Domination, Married Women, 'Indians': Part Three - “Indians”

An essay on two paths in property law: “marriage and family law” on one side and "federal Indian law" on the other

Here is one of the curious anomalies that make legal history so intriguing. Two areas of law apparently widely separated are in fact creatures of a single complex set of ideas and practices: “marriage and family law” on one side and "federal Indian law" on the other.

In Part One, we looked at “property” in legal theory.

In Part Two, we delved into “marriage and family law”.

In this Part, we explore US “federal Indian law”.

The core legal issue in colonial and revolutionary America was how to convert Native lands into ‘real estate’

The struggle to possess Native lands was not simply a physical struggle over occupancy and use, but an intellectual / legal struggle to impose a way of thinking about land, occupancy, and use.

William Cronon’s Changes in the Land (1983), which we quoted in Part 1 of this series, explains how ‘real estate’—the abstract notion of land as a marketable commodity—came to dominance in the colonies by the end of the 17th century. Cronon’s research is a momentous study of the ecological consequences of this development.

Johnson v. McIntosh (1823), one of the most significant cases in all of United States law, was provoked by a land transaction between colonists and Natives. Johnson laid a foundation upon which all land titles in the US rest, to this day.

The decision simultaneously laid the foundation for what is now called “federal Indian law” by imposing on the Original Peoples a “diminished sovereignty” over their lands, transforming Native Peoples from owners into “occupants” in their own territories. The court deceptively named this diminished status as “Indian title”.

Johnson was decided just four years after the publication of Tapping Reeve’s Baron and Femme, the first American treatise on “domestic relations” law that was the focus of Part 2 of this series. As we will see, these two documents mark the shifting legal ground between feudal and market understandings of property. On one hand, a shift away from feudalism in husband - wife relations; on the other hand, an extension of feudalism in US - Indigenous Peoples relations.

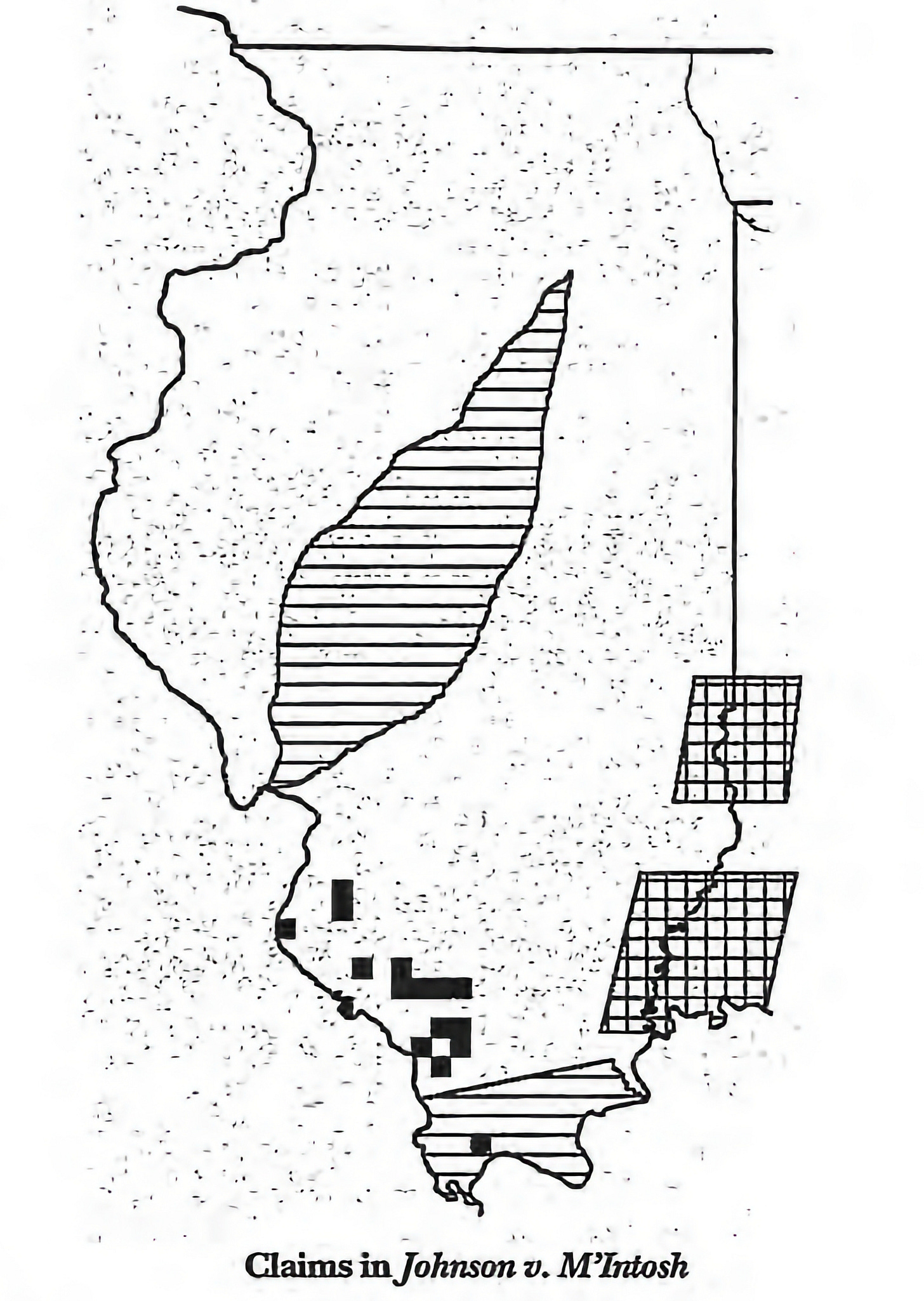

Johnson v. McIntosh involved a sham1 dispute set up between a plaintiff group of land speculators who claimed title to land under a purchase they had made from the Piankeshaw Nation in the region now called Indiana and Ohio, and a defendant who claimed supposedly the same land under a grant from the United States. The issue was which claim of title would be sustained, the purchase or the grant?

Three points stand out that illuminate our study of property law:

The purchasing group knew they were engaging in a land transaction on the cusp between feudalism and market economy.

The decision about US property law was based on the feudal conception of the power of a “Christian sovereign”.

The court denied Native property rights on grounds similar to those used to limit the property rights of a married woman (femme covert).

One: That the purchasers from the Piankeshaw knew they were on a watershed between two different notions of property is evidenced by the words they used to describe the transaction in a remarkably verbose clause of the deed of sale:

On the 18th of October, 1775, Tabac, and certain other Indians, all being chiefs of the Piankeshaws, and jointly representing, acting for, and duly authorized by that nation,…did, by their deed poll, duly executed,... and at a public council there held by them, for and on behalf of the Piankeshaw Indians, with Louis Viviat, of the Illinois country,... and for good and valuable considerations, in the deed … mentioned and enumerated, grant, bargain, sell, alien, enfeoff, release, ratify, and confirm to the said Louis Viviat, and … other persons … mentioned, their heirs and assigns, equally to be divided, or to George III., then King of Great Britain and Ireland, his heirs and successors, for the use, benefit, and behoof of all the above mentioned grantees, their heirs and assigns, in severalty, by which ever of those tenures they might most legally hold, all those …tracts of land, in the deed particularly described....

The verbosity was a sign of the confused and changing legal world of property law. The purchasers, unsure of their legal position, tried to cover all the bases. The words — "grant, bargain, sell, alien, enfeoff, release, ratify, and confirm" — were alternative bases for enforceability of the transaction. Verbs for transactions in the emerging economy of "private property" were mixed with verbs from the old structure of feudal property. On one hand, they stated claims as individual actors free from obligations to a feudal lord, and on the other hand as vassals subject to the “King of Great Britain”.

Intriguingly, they stated their ambiguity about their legal status as ambiguity about the actions of the Piankeshaw. If the purchasers were free from their king, then the Piankeshaw did "grant, bargain, sell, [and] alien" the tracts of land. If the purchasers were vassals, the Piankeshaw did "enfeoff, release, ratify, and confirm." Legal uncertainty produced a profusion of possible verbs, the purchasers hoping thereby to guarantee that they, "their heirs and assigns," would have this land "by which ever of those tenures they might most legally hold."

Two: Johnson v. McIntosh ruled in favor of the defendant’s claim of title under a grant from the US. The decision said the plaintiffs could not have acquired title by purchase—as individuals or as vassals—because the Piankeshaw had no land to sell: ‘Indians’ do not own their lands; the US owns Native lands.

Chief Justice Marshall, author of the opinion, explained how the US claimed title to Native lands via the doctrine of "Christian discovery” that had been developed by the Christian monarchs of Europe.

He wrote:

[In] 1496,… a commission [was issued] to the Cabots to discover countries then unknown to Christian people and to take possession of them in the name of the King of England. …To [Cabot’s] discovery the English trace their title. …

The right of discovery given by this commission is confined to countries "then unknown to all Christian people," and of these countries Cabot was empowered to take possession in the name of the King of England. Thus asserting a right to take possession notwithstanding the occupancy of the natives, who were heathens, and at the same time admitting the prior title of any Christian people who may have made a previous discovery.

The … principle continued to be recognized. The charter granted to Sir Humphrey Gilbert in 1578 authorizes him to discover and take possession of such remote, heathen, and barbarous lands as were not actually possessed by any Christian prince or people. This charter was afterwards renewed to Sir Walter Raleigh in nearly the same terms.

By the charter of 1606, under which the first permanent English settlement on this continent was made, James I granted to Sir Thomas Gates and others those territories …[which] were not then possessed by any other Christian prince or people. …

The United States…has unequivocally acceded to that great and broad rule by which its civilized inhabitants now hold this country. They hold and assert in themselves the title by which it was acquired.

In short, the Johnson decision took the Crown of feudal England and placed it on the US.

According to the theory of the British constitution, all vacant lands are vested in the crown… and the exclusive power to grant them is admitted to reside in the crown, as a branch of the royal prerogative. …This principle was as fully recognised in America as in the island of Great Britain. ... So far as respected the authority of the crown, no distinction was taken between vacant lands and lands occupied by the Indians.

Odd as it seems, Marshall, having positioned Christianity as the ground for claiming a right of property domination, also relied on it as “compensation” for that domination:

The potentates of the old world found no difficulty in convincing themselves that they made ample compensation to the inhabitants of the new, by bestowing on them civilization and Christianity, in exchange for unlimited independence.

Three: The feudal structure of the "discovery doctrine" echoes the feudal status of a femme covert dominated by her baron.

From Tapping Reeve’s Baron and Femme:

A wife cannot so contract, as to bind herself; her contracts are said to be void in law. The principles on which this doctrine is founded are two : 1st. The right of the husband to the person of his wife. … 2d. The law considers the wife to be in the power of the husband; it would not, therefore, be reasonable that she should be bound by any contract which she makes during the coverture….

Both Natives and femme covert are subjected to an “ascendant” power. The basic principle is the same in each instance: formerly free and independent beings become bound by others: in the case of the Natives, their property is no longer their own; in the case of wives, their persons are subjected to their "barons."

But the two fields of law were moving in opposite directions.

Reeve argued for expanding a wife's powers. As we saw in Part 2, he was highly critical of the rule that a wife cannot make a will. He said it was unreasonable that a femme sole (single woman) could write a will that would be nullified by her marriage. Reeve’s critiques of such feudal doctrines were a significant part of the eventual movement away from feudal definitions of women in US law.

Marshall, on the other hand, argued that “Christian Discovery” feudalism was unalterably the basis of US property law:

However extravagant the pretension of converting the discovery of an inhabited country into conquest may appear…[and] the concomitant principle, that the Indian inhabitants are to be considered merely as occupants.... [and] however this … may be opposed to natural right, and to the usages of civilized nations, yet, if it be indispensable to that system under which the country has been settled, and be adapted to the actual condition of the two people, it may, perhaps, be supported by reason, and certainly cannot be rejected by Courts of justice.

If we were to continue this comparison of feudal laws in two domains, we could examine Reeve's analysis of the law of guardian and ward for further insights into "federal Indian law." In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), Chief Justice Marshall suggested that the "special relationship" between the "Indian tribes" and the United States "resembles that of a ward to his guardian." This suggestion became a new doctrine that, like “Christian Discovery”, continues to be used as the legal excuse for an array of laws “governing” Native Peoples.

Eric Kades demonstrated that mapping the parties’ claims as enumerated in the district court records “shows that the litigants' land claims did not overlap. Hence there was no real 'case or controversy,' and Mclntosh, like another leading early Supreme Court land case, Fletcher v. Peck, appears to have been a sham." {See: "The Dark Side of Efficiency: Johnson v. M'lntosh and the Expropriation of Amerindian Lands," 148 University of Pennsylvania Law Review 1065, 1092 (2000). See also "History and Interpretation of the Great Case of Johnson v. M'lntosh." Law and History Review. Vol. 19. No. 1 (Spring 2001). which includes a map of the various claims.}

Lindsay Robertson called Johnson “a collusive case, an attempt by speculators in Indian lands to…win a judgment from the Supreme Court recognizing their claim to millions of acres.” {See: Lindsay Gordon Robertson, Conquest by Law: How the Discovery of America Dispossessed Indigenous Peoples of Their Lands (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), xi.}

To prevent the Court from discovering their collusion, the conspirators filed something called a “case stated,” which today is called a “joint stipulation of facts.” They did this to force the Court to choose between their competing legal theories even though there was no actual land dispute. They wanted the Court to settle a question that was crucial for all land speculators: How could non-Natives acquire ownership of Native lands under U.S. law?

I discuss other 'sham' aspects of the case in "John Marshall: Indian Lover?", Journal of the West, vol. 39 no. 3 (Summer 2000).] For example, the technical nature of the action, ejectment, was a "highly fictitious" common law action to restore possession of property. Despite the fictitious aspects of the case, its doctrine has been sustained to this day.

The more I read, the more my brain became frazzled, which I have long believed to be the real intent of legalese. We ordinary schmucks do not read the entirety of the 'terms and conditions.' We just click 'accept.' In other words, the concept of 'legality' is an artificial construct of 'civilization,' and should, therefore be erased from our species' vocabulary, allowing us to return to the ways we practiced for countless millennia before that infamous 'Dawn.'

Another substantial addition to our understanding of our history and the manipulation of law and relationships to divide and conquer native tribes in the US, usurping the land and forcing family groups to make consequential decisions along unfamiliar racist and pro-American guidelines. Thanks, Peter