"Inclusion" is not the same as Self-Determination — and may undermine it

The rights of Native people as US citizens are inconsistent with the rights of Original Peoples as peoples.

IN THIS POST: Exploring the complexities and contradictions of ‘multiculturalism’ and ‘multinationalism’ in relation to Original Peoples dominated by the US

I mulled over this post for weeks, moving toward and away from sending it.

My mulling started months ago when I saw the July / August 2023 Yale Alumni Magazine’s cover story featuring Mohegan Chief Marilynn Malerba’s 2022 appointment as Treasurer of the United States.

When Chief Malerba was appointed Treasurer, US Senator Brian Schatz (D-Hawai‘i), chairman of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, said:

Chief Malerba’s historic appointment affirms the administration’s ongoing commitment to empowering Native leadership at the highest levels of the federal government.

The NYPost said:

With Malerba’s appointment, it will be the first time in US history that a Tribal leader and Native woman’s signature will be seen on newly printed currency.

The Post added:

The president has actively taken steps to express a commitment to Tribal nations in his administration, including through naming Deb Haaland as the first Native American to lead the Interior Department.

I know that lots of people share these attitudes, also expressed by a commenter on the Yale magazine article: “Native North Americans are now taking their place in the running of these lands.”

But questions nagged at me:

When colonized people participate in the politics of their colonizer, does that signify the end of colonialism or its successful culmination?

Does the appointment of a ‘Native American’ to high office in the US government signify the ultimate success of the assimilation project?

What does such an appointment signify about the relationship between the US and Original peoples?

It is not an issue for me that Native people are following different paths in dealing with the US.

What is an issue is the widespread failure among Native and non-Native people to understand that ‘diversity and inclusion’ in the US system is not the same as Indigenous self-determination — ‘Indigenous sovereignty’.

This is a tricky difference to understand in light of the conventional rhetoric about ‘Tribal rights’ and ‘minority rights’; but it is a fundamental difference.

I’m glad I waited to publish this post until after recently discovering a 2016 law review article by Professor Rebecca Tsosie, “The Politics of Inclusion: Indigenous Peoples and U.S. Citizenship”.

Tsosie asks the question:

…whether the rights of American Indian and Alaska Native peoples as U.S. citizens are consistent with the rights of indigenous peoples.

She says:

Although all Native Americans are U.S. citizens today, they have a particular status, informed by historical circumstances, that defies the notion of equal citizenship.

Tsosie explores the tensions between ‘multiculturalism’ and ‘multinationalism’ and presents a wide-ranging review of theories about citizenship, sovereignty, and self-determination in a global context.

Tsosie’s article helped me take the step to publish this post because she provides such a depth of material about the situation, bolstering my insistence that fundamental choices are being masked by conventional (and often superficial) rhetoric.

Confusion about the difference between Original Peoples’ rights and ‘minority rights’ — as evident in the ‘BIPOC’ acronym that conflates Black, Indigenous, and People of Color — poses a threat to the legal status of Original Peoples.

Conflation of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color is a misguided expression of an allegedly postcolonial effort to celebrate pluralism and multiculturalism. It undermines the unique land-based status of Original Peoples.

Conflating Original Peoples’ rights with “minority” rights obscures a critical legal issue. To state it baldly, Original Peoples’ rights are not minority rights.

Minority rights — civil rights — refers to the equality of individual citizens under the US Constitution.

Original Peoples’ rights, in contrast, are group rights and are not based on the US Constitution, because Original Nations existed before the Constitution.

As Tsosie puts it:

The tendency to “racialize” American Indian political identity can be used to limit, rather than further, Indigenous self-determination.

Let’s start at the beginning: US anti-Indian law

When John Marshall wrote the opinion in Johnson v. McIntosh (1823) — the original US Supreme Court federal anti-Indian law decision — he said the relations between the colonizing "Christian discoverers" and the Original Peoples (he called them “inhabitants”) were "regulated" by the "discoverers."

This is the infamous "Doctrine of Christian Discovery”.

Johnson was a property law case. It declared that the Christian colonizers held “title” to the continent and therefore “owned” all Original peoples’ lands.

Johnson v. McIntosh still stands. It and its offspring are cited over and over again in US courts at all levels.

So, to repeat the question, what does it mean when Native people participate in American political processes?

John Marshall discussed the possibility that colonizers and Original Peoples might one day "mingle with each other; the distinction between them … gradually lost, and they make one people."

Even as he wrote that decision, the federal government was enacting “Indian Removal” and “Civilization” programs.

Marshall’s vision of “mingling with each other” became the dominant theme of US “Indian policy”. It bore such wicked fruit as the compulsory detention centers called “boarding schools”, guided by the infamous mantra of Richard Henry Pratt, “Kill the Indian and save the man”.

Pratt’s ‘boarding school’ program aimed to break the transmission of Indigenous languages and traditions, with the goal of incapacitating Indigenous cultures and political structures through a multi-generational process.

“Removal” and “Civilization” combined to undermine the free existence of Original peoples.

The 1924 Indian Citizenship Act, often praised as an affirmation of Original peoples’ rights, was part and parcel of the program to assimilate Original Peoples as individuals into US society and pave the way for the termination of Original Peoples as separate political entities.

Tsosie quotes Professor Bethany Berger:

Efforts to grant U.S. citizenship to American Indians were “repeatedly linked to efforts to deny them self-determination.”

“Citizenship was the triumph of assimilation and the opposite of indigeneity.”

Tsosie says:

Indigenous self-determination as a political movement… consciously rejects multiculturalism in favor of … multinationalism, that is, the construction of a … consensual [international] political order in which indigenous peoples are included as distinctive sovereign governments entitled to equal respect.

The Onondaga Nation and the Haudenosaunee led the way in rejecting the Citizenship Act and resisting its implementation immediately after its adoption. They explained this history in a 2018 statement, “The Citizenship Act Of 1924 Was An Integral Pillar Of The Colonization And Forced Assimilation Policies Of The United States In Violation Of Treaties”.

By 1946, when President Harry Truman signed the Indian Claims Commission Act, the rhetoric of “killing the Indian” had fully morphed into “equality”.

Truman said:

[Now] Indians can take their place … in the economic life of our nation and share fully in its progress.

Three years later, Truman sharpened the point when he vetoed a bill intended to provide aid to the Navajo and Hopi nations.

He said

Our policy [is to assist] the Indians to develop their natural talents and physical resources in ways that will enable them to participate fully in our free, but vigorously competitive, society. . . .

In the long run, this process of adjustment to our culture can be expected to result in the complete merger of all Indian groups into the general body of our population.

Participating in US politics implies – indeed, it affirms – that the participants are part of the US political system; Native people sometimes say they want a “voice” at the dominator’s table to help decide what the US does to Original Peoples.

In contrast, Original Nations struggling against US domination are trying to take their lands and lives off the dominator’s table altogether.

There are many voices pushing the “voice” path, including the major campaign to persuade the US Congress to enact the Native American Voting Rights Act.

I am not writing to take sides between these approaches. I am writing to clarify that they are on two different paths.

Indigenous self-determination — call it sovereignty if you will — is not fundamentally a civil rights “minority” issue.

Vine Deloria, Jr., explained this in his 1974 Behind the Trail of Broken Treaties:

Few people [in America] were able to . . . recognize that if the United States and its inhabitants . . . regarded the Indians as another domestic minority group, the Indians did not see themselves as such.

Tsosie closes with a critique of the notion of the “cosmopolitan citizen” promoted in much contemporary rhetoric about “diversity”:

The cosmopolitan citizen …[is not] defined by … location or … ancestry or … citizenship or … language.

She says:

Think about how powerful that statement is. In fact, [it] is the antithesis of what indigenous advocates are arguing for in the context of self-determination and the demand to have their cultural integrity respected by enforceable rights.

How do we apply these thoughts to the situation of Original peoples and America?

When a Native person speaks about "my country," what country is being talked about? Is it an Original Nation or the United States?

When political parties jockey for the “Native vote”, are they supporting or undermining Indigenous self-determination?

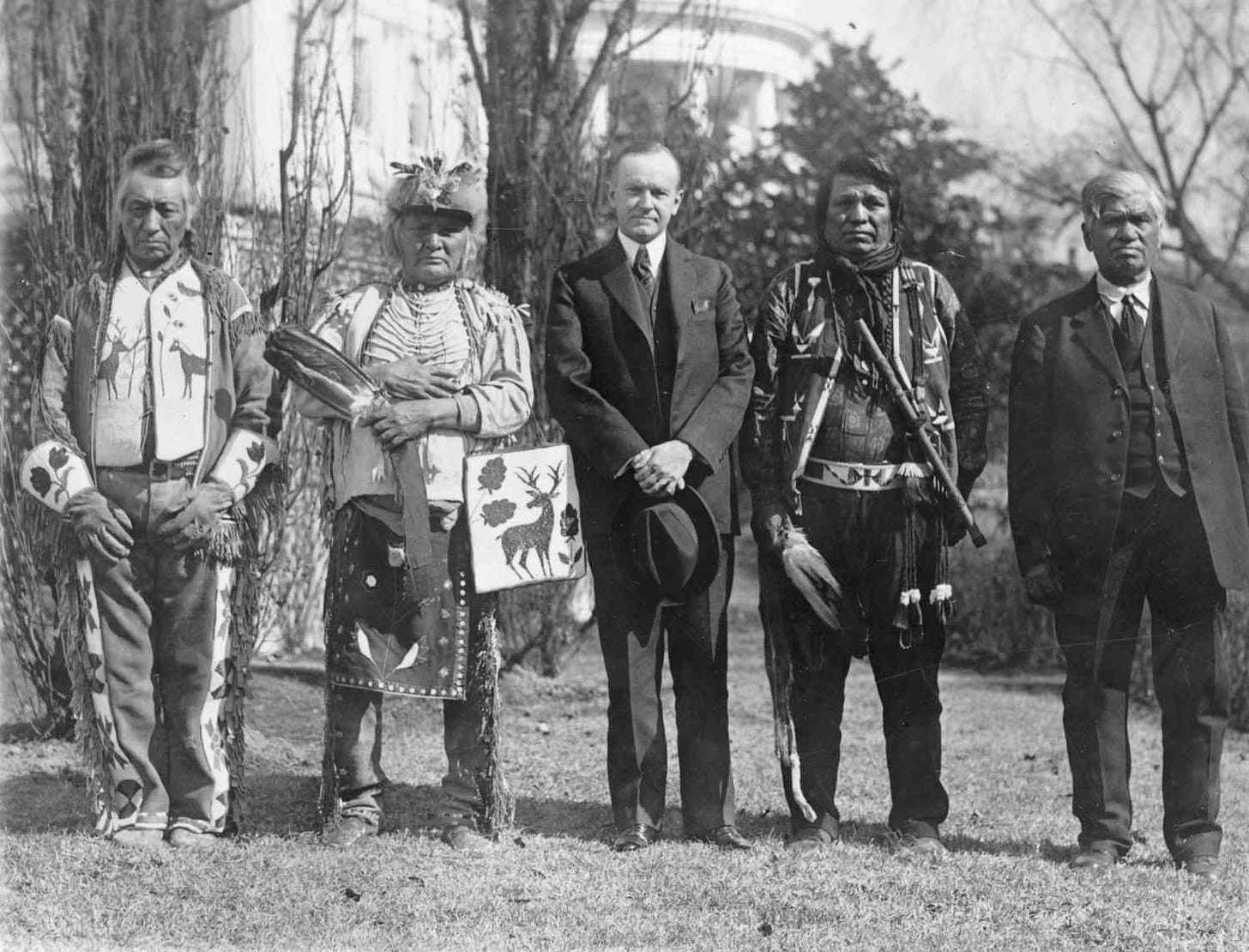

When a ‘Native American’ is in high office in the US government, does this signify Indigenous success or the success of the colonization assimilation project?

It may well be the case that a Native person values US citizenship and seeks an active role in the political system that dominates Original nations. But it is an approach fraught with difficulty because it can trap that person in an illusion of self-determination and cause them to miss opportunities for the real thing.

Prof. Peter D'Errico makes an outstanding point of substantive differentiation. 'Inclusion' is a first cousin to 'collaboration' (double entendre that it is) in the smoke-filled clutter of contemporary 'progressive' rhetoric. Self-determination is the fact of the matter and also gets to the very heart of the fundamental values at play.

i completely agree with this article; thinking about this subjects often, another, perhaps a tag off the original sentiment, that citizens do not have treaties with their own governments...the tell-tale evidence will be to what extent does the the observance of treaty, treaty protocol, and the constitutional mandates affirming treaties with Indian Country manifest. To date treaties and the subject thereof is never a topic of discussion, nor promise by the government. There is no prerogative to treaty implementation other than implementation...over 800 treaties with Indian Country between the u.s. and canada, and to date, not one is enforced by each colonial settler nation state....the next chapter in this historical soap opera, is what would life look like if those treaties were/is the relationship....