Corporate Personality and Human Commodification - Part 1 (of 3)

Christianizing Indians, Corporatizing America... overlapping agendas for empire

At the top of the city

in a glass-chromed room

an attorney assures the board of directors

that the corporation is the person

against which any or all action may be taken,

not against each and every director joint or several. The multiheaded person exhales dry-iced victory as counsel backs out the door

descending floor after floor

to wait for a cab in the cold.

Nearby a breathing bundle of rags

sits on a grate of steam

and waits just waits

wondering where warmth went.

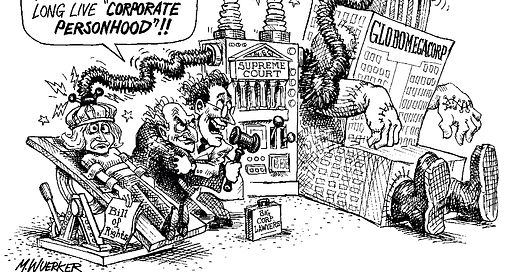

—Ruth Knight, "Persons"Ruth Knight wrote this poem for an essay I wrote three decades ago, “Corporate Personality and Human Commodification”, exploring the US Supreme Court case of Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819).

Dartmouth College adopted the concept of “corporate person” into US law.

I presented the essay to a group ‘Marxist’ economists at UMass Amherst, who encouraged me to submit it to their journal, Rethinking Marxism, where it appeared in 1996. I subsequently posted it on my UMass Amherst website.

I’ve always thought Ruth’s poem stands by itself as an indictment of the “corporate person”.

But if you’d like some analysis, here’s Part 1 of a revised version of the essay…

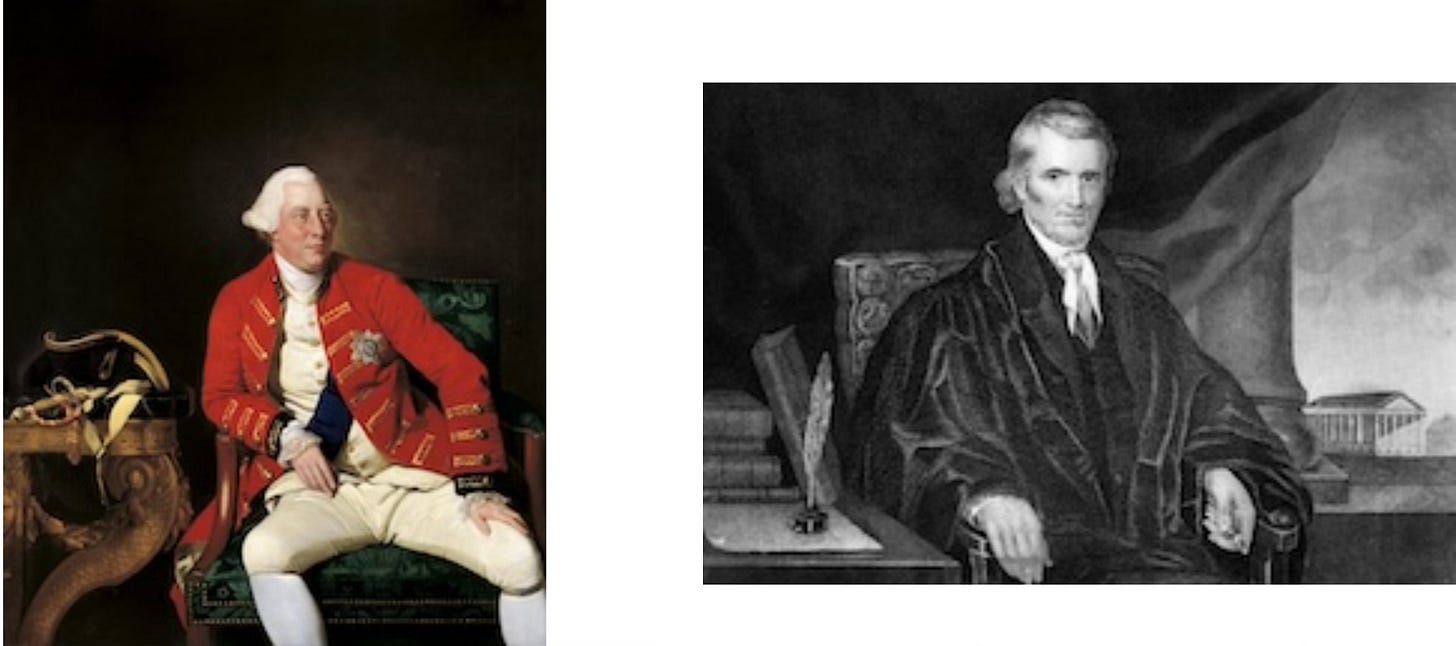

The Monarch and the Federalist

The story of Dartmouth College v. Woodward begins with a December 1769 royal charter that “George the Third, by the grace of God, of Great Britain, France and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, and so forth,” issued “in the 10th year of his reign”:

KNOW YE, THEREFORE, that We, considering the premises, and being willing to encourage the laudable and charitable design of spreading Christian knowledge among the savages of our American wilderness, and also that the best means of education be established in our province of New Hampshire, for the benefit of said province, do, of our special grace, certain knowledge and mere motion, by and with the advice of our counsel for said province, by these presents, will, ordain, grant and constitute, that there be a college erected in our said province of New Hampshire, by the name of Dartmouth College, for the education and instruction of youth of the Indian tribes in this land, in reading, writing and all parts of learning, which shall appear necessary and expedient, for civilizing and christianizing children of pagans, as well as in all liberal arts and sciences, and also of English youth and any others.

King George added:

And we do further will, ordain and direct that the president, trustees, professors, tutors and all such officers as shall be appointed for the public instruction and government of said college shall, before they undertake the execution of their offices or trusts, or within one year after, take the oaths and subscribe the declaration provided by an act of parliament made in the first year of King George the First, entitled "an act for the further security of his majesty's person and government, and the succession of the Crown….” [an oath of allegiance to His Majesty and the Church of England].

In June 1816, the New Hampshire legislature, having thrown off decades earlier its allegiance to the Crown and rejected any royal claim to the “province”, enacted a law “to amend the charter, and enlarge and improve the corporation of Dartmouth College."

The law said:

" Whereas, knowledge and learning generally diffused through a community, are essential to the preservation of a free government…and … the college of the State may, in the opinion of the legislature, be rendered more extensively useful: therefore…

The corporation, heretofore called and known by the name of the Trustees of Dartmouth College shall ever hereafter be called and known by the name of the Trustees of Dartmouth University;…

Be it further enacted that the President and professors of the University…shall take the oath to support the Constitution of the United States and of this State….

The Trustees of the College met in August 1816 and “voted and resolved…that they do not accept the provisions of the said act of the legislature of New Hampshire [creating the University]….” They said they “still claim the right of acting” under the royal charter.

When New Hampshire’s highest court ruled for the state University, the College Trustees appealed to the US Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court “reversed and annulled” the New Hampshire court’s decision, in an opinion by Chief Justice John Marshall.

Marshall made a three-step argument:

The 1769 British Crown charter was a “contract” creating a “private institution”.

The contract is protected by the US Constitution, Article I, Section 10, Clause 1, which includes the following words: “No State shall…pass any…Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts….”

The Act of the New Hampshire legislature altering the charter without the consent of the corporation … is a law impairing the royal contract, and is therefore unconstitutional and void.

In a nutshell, Marshall said that notwithstanding the American Revolution overthrowing the claims of the British Crown to the territory of North America, the Revolution did not overthrow contracts made by the Crown with parties in those territories.

In short, Dartmouth College subordinated a state legislature to a Crown corporation.

Marshall ruled that Crown corporations not only survived the American Revolution, they were protected by the US Constitution.

Marshall says corporations are “immortal beings”

Marshall elaborated on his conclusion that the British Crown corporation was a legal entity that even the American Revolution could not displace or terminate.

He said:

A corporation is an artificial being, invisible, intangible, and existing only in contemplation of law….

Among the most important [of a corporation’s properties] are immortality, and, if the expression may be allowed, individuality; properties, by which a perpetual succession of many persons are considered as the same, and may act as a single individual.

It is chiefly for the purpose of clothing bodies of men, in succession, with these qualities and capacities, that corporations were invented….

By these means, a perpetual succession of individuals are capable of acting…. like one immortal being.

But get this: Marshall added that:

This … immortality no more confers on it political power, or a political character, than immortality would confer such power or character on a natural person.

🤯 Wow! What are we to make of this bizarre assertion?!

Across cultures of every variety, only gods are presumed to be “immortal”.

The immortality of gods is the most intense contrast to the mortality of “natural persons”.

The Dartmouth College decision placed corporations on a level with gods… and then said this godlike quality was nothing special!

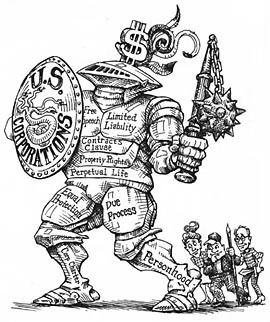

The concept that a corporation is an "immortal person" is the legal core of corporate power.

Within a few decades of the Dartmouth College decision, the power of “immortal”corporations had become obvious: corporations were major institutions, rivaling governments.

Populist legislatures responded to corporate power with a variety of legal obstacles to and special taxes on corporate business.

Corporations responded with a barrage of litigation aimed at stretching the US Constitution to prohibit all state regulation.

In 1886, the Supreme Court issued a clear victory for corporations in Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad, a populist tax case.

Santa Clara went beyond Dartmouth College.

It declared that the Southern Pacific Railroad was not only a "person" for Constitutional contract protection but was a “person” under the Fourteenth Amendment, with rights to life, liberty, property, due process and equal protection.

The court was curt:

"The court does not wish to hear argument on the question whether the provision in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which forbids a State to deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws, applies to … corporations. We are all of opinion that it does".

Legal philosophers erupted with questions about “real” and “artificial” persons.

John Dewey said in 1926 that the notion of “legal personality” raised questions not only about corporations (and the state) but also about humans, "natural persons." He said a “natural person” was not necessarily the same as a “person” in the legal sense.

Dewey called for an “overhaul [of] the [legal] doctrine of personality which underlies both” natural and corporate “persons”.

By mid-20th century, the philosophical trauma and search for a coherent legal theory resolved into a consensus that corporations and "natural persons" should be treated the same, and that it was not necessary to ask difficult questions about the "meaning" of “person”.

Dewey suggested that judges and legislators don’t need to worry about the fact that there is “no general agreement” about legal “personality”.

He said they should just keep making laws and “do their work without … any conception or theory at all”.

But the Circuit Court opinion in Santa Clara that the Supreme Court said it did not “wish to hear argument” about actually did provide a legal theory.

The court said corporate and natural persons were in the same legal boat.

It set out its justification for this proposition in a series of florid hypothetical statements about varieties of tax discrimination, ultimately saying that discrimination between corporations and natural persons is as evil as discrimination between natural persons.

Pay attention to the semantic structure of the justification:

The court smoothly elides the distinction between individual economic activity and the activity of economic organizations.

The court neatly equates differences of economic function with human differences.

The court intertwines signs of natural human difference — race, sex, age — with signs denoting types of institutions and forms of business organization.

In this way the Circuit Court permitted no distinction between humans and human organizations, between biology and politics—one was included within the other.

The court subsumed human existence in the abstract realm of political economy.

This semantic movement reached its foreordained conclusion: the concept of human equality in the Fourteenth Amendment not only extended to the nonhuman but prohibited any distinction between human and nonhuman, between humans and corporations.

Here’s the justification:

It would be a singular comment upon the weakness and character of our republican institutions if the valuation and consequent taxation of property could vary according as the owner is white, or black, or yellow, or old, or young, or male, or female...

Strangely, indeed, would the law sound in case it read that in the assessment and taxation of property a deduction should be made for mortgages thereon if the property be owned by white men or by old men, and not deducted if owned by black men or by young men; deducted if owned by landsmen, not deducted if owned by sailors; deducted if owned by married men, not deducted if owned by bachelors; deducted if owned by men doing business alone, not deducted if owned by men doing business in partnerships or other associations; deducted if owned by trading corporations, not deducted if owned by churches or universities; and so on, making a discrimination whenever there was any difference in the character or pursuit or condition of the owner.

To levy taxes upon a valuation of property thus made is of the very essence of tyranny, and has never been done except by bad governments in evil times, exercising arbitrary and despotic power.

The court repurposed the logic of the 14th Amendment emancipation of Black slaves into a generic logic of nondiscrimination and cloaked that transformation in religious imagery — befitting a concept that corporations are like gods:

With the adoption of the [Fourteenth] amendment the power of the state to oppress any one under any pretense or in any form was forever ended; and henceforth all persons within their jurisdiction could claim equal protection under the laws….

This protection attends every one everywhere, whatever be his position in society or his association with others, either for profit, improvement, or pleasure.

It does not leave him because of any social or official position which he may hold, nor because he may belong to a political body, or to a religious society, or be a member of a commercial, manufacturing, or transportation company.

It is the shield which the arm of our blessed government holds at all times over every one, man, woman, and child, in all its broad domain, wherever they may go and in whatever relations they may be placed.

The court refused to discuss Populist objections to vast corporate aggregations of wealth. Instead, it asserted that gigantic corporations have a beneficial impact on people's lives:

"The aggregate wealth of all the… companies engaged in business, or formed for religious, educational, or scientific purposes, amounts to billions upon billions of dollars… and furnishes employment, comforts, and luxuries to all classes, and thus promotes civilization and progress… the persons composing them—amounting in the aggregate to nearly half the entire population of the country".

In short, populist battles against corporate power were derailed in the name of freedom.

The court portrayed the corporate person as a benevolent Titan, allied with humanity in a struggle for material prosperity and endangered by foolish legislators.

There was no acknowledgment in the court's opinion of any dangers posed to humanity or the planet by corporate tyranny.

Stay tuned:

Part 2: The Political Economy of Corporate Personality

brilliant beyond words - thanks for adding clarity to this concept

Oh, wow! I can’t wait to read the rest. The idea of the legal rights of corporate persons has done so much mischief. Thanks for giving us what looks to be a clear and accessible guide on this issue.