“What we call the ‘Indian way of life’ is only a human being way of life.”

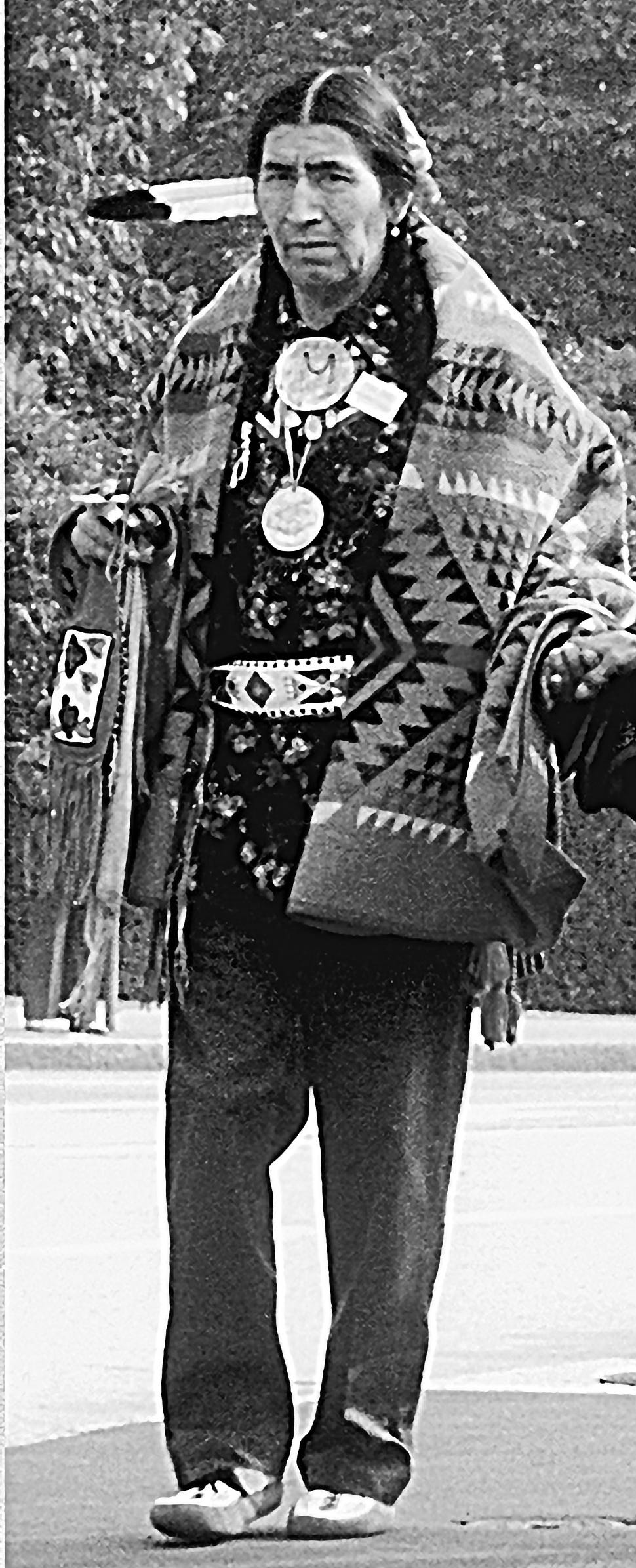

...inspiration from Phillip Deere...

I sent the ingredients of this post as an email to my subscribers…

… now I want to share it with all readers.

I have moved across country... ...and am contemplating moves in my writing...

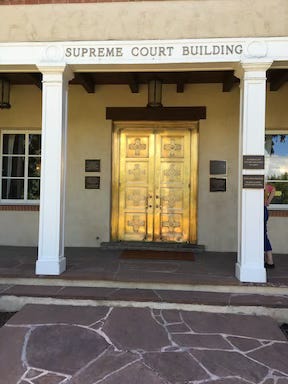

Greetings from Santa Fe, where we now live, having left our home of 40+ years in western Massachusetts…. Rested and almost unpacked… we are enjoying living in the place where my law career started:

I took the bar exam at the New Mexico Supreme Court in 1969, when I was a staff attorney at Dinébe’iiná Náhiiłna be Agha’diit’ahii (Navajo Legal Services).

Many of you know from my book how experiences in Navajoland shaped my legal and academic career… and pointed me in a direction I still follow.

Most of my writing to date has focused on legal / academic analysis. One exception was

20/20 at Big Mountain: How Television Tried to Craft a Narrative of Indigenous Reality ... and Failed

It was June 1986. I was at Big Mountain / Black Mesa returning with my sons Julian and Adrian and my wife Angela to the land where I first encountered “India…

my recent Substack piece about mass media at Big Mountain.

Several readers referred to it as a “new genre” of my writing… and encouraged me to do more “personal” writing.

Their suggestions resonated with a sense already percolating in me to step back from an almost single-minded emphasis on legal and academic essays to write more broadly — personally, philosophically.

The broader perspective would still have roots in my legal / academic experiences with Original Peoples and Nations, building from something Muscogee Creek medicine teacher Phillip Deere said:

“What we call the ‘Indian way of life’ is only a human being way of life.”

🌈 Those of you who have read my book will recall this personal example:

One day I spoke to a group of parents at Teec Nos Pos about the possibility for them to take control of the local school, replacing the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. Frank Begay, a Navajo Tribal Court advocate, was translating. An older man, he was also the go-to person for other advocates who needed help with translating. …

When I finished my talk … several people spoke up. Frank leaned in and told me, “They want to know more about you.” Thinking that I had been unclear in describing the case or how DNA lawyers might work with them, I began to say more about DNA and legal services.

Frank stopped me. “That’s not what they’re asking about. They want to know more about you personally: Where were you born? Do you have brothers or sisters? Things like that.”

I still feel a surge of emotion as I recall the event. I was flabbergasted. I felt shock and surprise. I felt embarrassed. I was thrilled. I had learned to isolate professional work and personal life; this was ordinary in American society and emphasized in legal education. I suddenly knew that these people were paying attention to me—not just as their lawyer, but to me as a human being. I felt alive, and I loved it.

From that time on, I worked with Frank as much as possible, because he was older and more traditional than other advocates, and he was with me for that first experience of being cared about as a person, not just as a lawyer. We traveled to meetings sometimes an hour or more away, and he told me stories about the places we passed, about the lives of people, about what it means to be human in the Navajo world, and about skin-walkers (a malevolent entity that can assume an animal disguise) and how to avoid them. Later, I learned how rare it was for a non-Navajo to be privy to this world.

⚡️Another example from my book shows how personal life can be illuminated by legal / academic analysis:

The Allotment Act was an explicit assault on the extended family, …an effort to impose the Western notion of individualism and nuclear family, the idea that a family consists of one woman, one man, and their children, living in one residence. As Professor Kristen Carpenter emphasized in “Real Property and Peoplehood,” her study of relationships between human beings and land, the individualist paradigm of property does not support peoplehood. The historian Rose Stremlau said, “The allotment debates were not about land; they were about the kind of societies created by different systems of property ownership.”

The lesson here is that the program (still ongoing) to destroy Indigenous peoples as peoples and to assimilate Indigenous persons as individuals illuminates the nature of US society.

To feel and understand relationships between people and land illuminates our lives.

That kind of illumination is what I have in mind as I contemplate the messages sent to me about my last post.

What do you think?

Please send me your thoughts…. suggestions … questions….

Thanks again for reading.

Peter

Another great read, Peter. As I know you know, most Indian speakers will often introduce themselves by including the separate names of their parents and birthplace before speaking... In my work with the Northern Pomo, I discovered that the structure of their language precluded the telling of falsehoods and subsequently they had no word for "lie" in their language. Fascinating and deeply distressing to know it is possible! james

I am so glad to read this, and am in complete agreement with the statement: “What we call the ‘Indian way of life’ is only a human being way of life". My heart has been screaming this for a long time. As we hurl ourselves further into merging with machines, I grieve for those who will never even be able to understand that life ( real life) is a gift and an opportunity. When we lose connection with our past ( or pretend it doesn’t matter) we lose the ability to see the gift for what it is.