What it means to “think like a lawyer.”

A legal realist view of law, lawyering, and legal change ...

A law school classroom is a crucible in which the scholarly interests of teachers mix with pressures from the practicing bar. The topics and questions in a class in any field of law range from explicitly practical questions—what is the law, how is it likely to develop?—to jurisprudential philosophy—what concepts, values, and assumptions underlie the law? Every law class confronts this mixture in proportions that vary according to the interests of the teacher, the students, and the current times. Let’s take a look through the lens of “legal realism”.

A Jealous Mistress with a Janus Face

Court opinions are central to legal education. Students learn to read past decisions, which are called “precedents”—literally, “that which precedes”—and to use what judges said in the past to build arguments to persuade judges in the present.

One key lesson that every law student learns is that no court opinion ever stands alone. Every opinion is interconnected with other opinions—those that the judge cites as precedent and those in which the opinion in turn is cited as precedent. In short, court opinions exist in lines of precedents and fields of doctrines.

The cognitive demands are enormous. Students read and sift through dozens, even hundreds, of cases; they have to determine not simply what the “final decision” was, but which words the judge wrote and which facts the judge alluded to were relevant to the decision. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that judges often write more than they need to reach a decision. Indeed, there is a concept called “obiter dictum” (sometimes shortened to “dicta”) that applies to incidental remarks in an opinion that are not essential to the decision.

The effort to make sense of the whole system of precedents—which is really what “thinking like a lawyer” means—requires students to bring their minds into a cognitive framework of authority centered around judges’ words.

Law students are urged to forget about everything except what judges have said and decided. Law students learn that what counts as “reason” in law is what has been decided by the highest courts. High court judges’ views are the ruling ideas, referred to as “doctrines”—literally, “teachings.”

Making the task even harder, students cannot assume that the cognitive framework is grounded in ordinary common sense or natural human relations. In the words of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, law is:

…a system . . . built up and perfected by artificial doctrines adapted and moulded to the artificial structure of society.

Abraham Lincoln’s advice to law students rang the same theme:

If you wish to be a lawyer, attach no consequence to the place you are in, or the person you are with; but get books, sit down anywhere, and go to reading.

One of the most famous statements about the demands of studying law was made by Justice Story in his 1829 inaugural address as Dane Professor of Law at Harvard University. He said:

I will not say . . . that ‘The Law will admit of no rival’ . . . but I will say that it is a jealous mistress, and requires a long and constant courtship. It is not to be won by trifling favors, but by lavish homage.

Story’s image of the law as a jealous mistress demanding all one’s attention was once commonly taught to first-year students in American law schools; now, in an era of concern for gender stereotypes, few law students hear Story’s words. Nonetheless, the image of a stern taskmaster prevails in the realm of legal education.

The conventional justification for Story’s description of law and society as “artificial” and Lincoln’s advice to ignore people and places and pay attention only to books is that this maintains consistency between present decisions and past decisions and thus ensures fairness and equal treatment “under law”.

But the question arises: How can law change if precedents bind decision-making?

Karl Llewellyn, twentieth-century law professor and scholar, offered a famous answer to this question in his 1951 introductory lectures to first-year law students, The Bramble Bush: On Our Law and Its Study.

Llewellyn said that the system of precedents is actually not closed and does not actually bind the present because every prior opinion is open to interpretation. He said that every court decision “is two-headed . . . Janus-faced”, referring to the ancient Roman god of gates and doorways, who looks both inside and outside, forward and backward.

What I wish to sink deep into your minds about the doctrine of precedent, therefore, is that it is two-headed. It is Janus-faced. That it is not one doctrine, nor one line of doctrine, but two, and two which, applied at the same time to the same precedent, are contradictory of each other.

That there is one doctrine for getting rid of precedents deemed troublesome and one doctrine for making use of precedents that seem helpful. That these two doctrines exist side by side. That the same lawyer in the same brief, the same judge in the same opinion, may be using the one doctrine, the technically strict one, to cut down half the older cases that he deals with, and using the other doctrine, the loose one, for building with the other half.

Until you realize this you do not see how it is possible for law to change and to develop, and yet to stand on the past.

Llewellyn said the way to “get rid” of a precedent we don’t like is to read it “strictly”, to “confine it to its facts” (the precedent applies only to those facts) so that it cannot apply in the facts in the case we are arguing.

Llewellyn said that a “strict” reading requires “fine . . . minds, minds with sharp mental scalpels.” He said that “an ignorant [or] unskillful” lawyer will find it hard to do a “strict” reading and will be bound by the past case.

In contrast, Llewellyn said, a “loose” reading of a judge’s opinion will quote any and every word as may seem useful to one’s present argument, even if it was obviously “dicta”. The “loose” way of reading is easy, he said, because there’s no need for parsing or close analysis.

In practice, Llewellyn pointed out, a lawyer or judge uses both methods, depending on the needs of the argument or the decision. His point for the students was that by understanding the “Janus-face” of precedent, they will have “the tools for arguing…as counsel on either side of a new case.”

This is probably one reason people criticize lawyers and judges—because they can talk out of either side of their mouths. But the fact is that this is the way legal stasis can transmute into legal change.

Moreover, Llewellyn said that whichever way a court reads a precedent in deciding a case “will be respectable, traditionally sound, dogmatically correct.” This, of course, is subject to the qualification that a higher court, on appeal, may read the precedent differently… and that reading becomes the “respectable, traditionally sound, dogmatically correct” reading. And then that precedent, in turn, becomes fodder for new arguments and readings in subsequent cases. And so on….

Awareness of the fact that every case can be read in different and contradictory ways reveals the indeterminacy of law and startles anyone who thinks that law is definite and predictable by some kind of rote application.

Llewellyn emphasized that law is not something “out there” that determines decisions; rather, law is an active process of argument, and every case involves “matters of judgment and persuasion.” He forcefully criticized the view that “precedent produces . . . certainty”:

People . . . who think that precedent produces . . . a certainty that [does] not involve matters of judgment and persuasion, or who think that what I have described involves improper equivocation . . . such people simply do not know our system of precedent in which they live.

Llewellyn invited students to resist the “jealousy” of law—not to follow the way of Story and Lincoln. He advised them to look outside the books, to look at persons and places, and to look at society as it is lived:

Use all that you know of individual judges, or of the trends in specific courts, or, indeed, of the trend in the line of business, or in the situation, or in the times at large—in anything which you may expect to become apparent and important to the court….

Llewellyn’s way of teaching and studying law was called “legal realism”. At its simplest, it said that judges “create” law, and not simply from books, but from experience. They use, but do not simply apply, preexisting law. In short, what courts do is law, and law does not exist apart from what courts do.

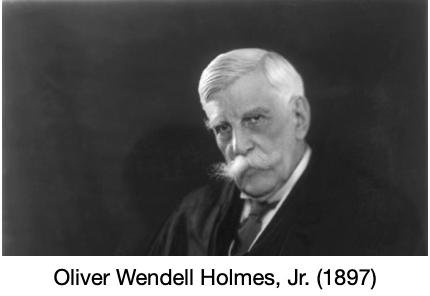

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., inspired the legal realist view in 1897 when he was an associate justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. He insisted that statements about law are only “prophecies of what the courts will do… and nothing more pretentious”.

In 1918, when he was an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, Holmes stated the realist view more formally:

For legal purposes a right is only the hypostasis of a prophecy—the imagination of a substance supporting the fact that the public force will be brought to bear upon those who do things said to contravene it.

In other words, to say there is a “right” to do something is to predict that a judge will rule in favor of doing that something—nothing more, nothing less.

The legal realist view rattles anyone who thinks that law exists somewhere apart from politics and economics and social trends. But this view is at the core of “thinking like a lawyer”.

The pedagogical dilemma in teaching law.

How can students be prepared to practice if they learn that doctrines are always subject to argument and are subject to gyrations under color of “the rule of law”?

The beginning of an answer to this question is to recognize that a proper legal education actually thrives on the indeterminacy of rules. A law teacher takes indeterminacy in stride as grist for class discussion. Teachers and students argue about the interpretation of rules and texts without worrying that their arguments undermine the rule of law, though they may accuse their opponents of doing just that.

In short, although the law looks like rules when viewed by outsiders, the law consists of arguments when viewed from inside.

This is especially true in the Anglo-American “adversary process,” where cases are viewed as contests and the parties are expected to present arguments as one-sided as possible. Baron Patrick Devlin, a British Law Lord, praised adversary process in his 1979 book, The Judge, where he said:

Two prejudiced searchers starting from opposite ends of the field will between them be less likely to miss anything than the impartial searcher starting at the middle.

Teaching, learning, and practicing law require engagement with the argumentative structure of law. The materials of law—cases, statutes, regulations, treaties, and so on—are bases for arguments. Indeed, the teacher’s selection and arrangement of materials already implicates arguments.

There is a special problem in all this for the public view of law, the “outsider” view. That is the need to sufficiently hide the internal argumentative process to maintain public support for the law as apparently a regime of rules.

The professional craft of lawyers and judges is to frame arguments and decisions around supposedly definite “rules” supposedly derived from established “doctrines.”

Facing the dangers of lawyering: challenging established legal doctrine.

It is one thing to argue legal doctrine in a classroom. It is another to challenge it in court.

Legal doctrine does not exist in a true/false dimension, but rather in an accepted/unaccepted dimension. The more lawyers who argue and judges who accept and enforce a doctrinal argument, the more “real” it becomes, and the harder it is to change or dismantle it.

Llewellyn explained in The Bramble Bush that a lawyer may regard a given doctrine as a “fossil” that does not deserve to be followed. “Challenge it you may,” he said, “But overlook it you may not.”

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure make it risky for a lawyer to argue against existing doctrines.

Rule 11(b)(2), titled “Representations to the Court,” mandates that an attorney’s argument must be “warranted by existing law or by a nonfrivolous argument for extending, modifying, or reversing existing law or for establishing new law.” Section (c) of the rule provides penalties for violating this mandate. A lawyer planning to challenge existing law must build “nonfrivolous” arguments.

Commentators have criticized Rule 11 for blocking vigorous creative lawyering. One commentator pointed to the fact that civil rights lawyers are more frequently penalized under Rule 11 than lawyers in other fields of law, indicating greater danger in litigating about rights.

Black’s Law Dictionary defines a “frivolous” lawsuit as one that is “groundless . . . with little prospect of success; often brought to embarrass or annoy the defendant.” A challenge to any entrenched doctrine will likely “embarrass or annoy” somebody, even when annoyance is not the purpose of the lawsuit. The lawyer will have to walk this fine line.

A historical example

As Llewellyn taught, doctrinal challenge requires not simply applying rules that jump out of cases but looking for fault lines and fracture points where past decisions can be limited, thereby opening the way to different decisions and doctrines.

In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court established the segregationist doctrine of “separate but equal” in the infamous case of Plessy v. Ferguson. The Plessy decision not only legitimized racial segregation in the United States, but it also described segregation as law “enacted in good faith for the promotion of the public good.”

“Separate but equal” remained entrenched in U.S. law until 1954, when the Supreme Court declared the doctrine unconstitutional in the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education.

Historians give major credit for the Brown decision to Thurgood Marshall, the lawyer who organized litigation across the country to challenge segregation (and whom President Lyndon Johnson later appointed to the Supreme Court). Marshall deserves high praise for mounting a daunting stand against legalized racism. But there is a longer history of challenges to “separate but equal” doctrine, starting immediately after the Plessy decision. Those challenges illuminate the importance of creative, aggressive lawyering (and courageous plaintiffs and defendants).

In 1898, only two years after Plessy, Joe Smith, a railroad conductor in Tennessee, appealed his conviction for “failing, neglecting, and refusing to assign certain negroes to the car and compartment of car used on the Louisville & Nashville Railroad for colored passengers, and for permitting them to ride in the car and compartment thereof assigned to white passengers.” Smith’s lawyers, from the law firm Smith & Maddin, argued that the Tennessee statute mandating “equal but separate accommodations for the white and colored races” was invalid because it interfered with interstate commerce, in violation of the U.S. Constitution’s provision for federal supremacy over control of such commerce. They argued that separate cars might be valid for in-state travel, but not for passengers riding into Tennessee from out of state. Notice that this argument did not attack racism per se; it offered a partial attack under a plausible, already existing (i.e., not “frivolous”) doctrine about interstate commerce.

The Tennessee Supreme Court rejected the challenge and upheld Smith’s conviction, quoting Plessy and saying that the statute requiring conductors of passenger trains “to assign to the car or compartments of the car . . . used for the race to which such passengers belong,” was not a regulation of commerce at all, but rather “reasonable legislation under the police power to provide for the health, safety, well–being, comfort, and morals of the public.”

The same year, Robert and Fannie Lander, represented by the law firm of John Feland & Son, sued a railroad in Kentucky for damages for forcing Mrs. Lander to either vacate her seat in the first-class Ladies coach, for which she had purchased a ticket, or leave the train. The Landers, whom the appeals court described as “colored people,” testified that when she refused, the conductor, “with two or three other men, who were also agents of [the railroad], . . . took hold of her by the arms, and shoved her up from it . . . proceeding by force of arms to remove her.”

The bold trial judge (in Christian County Circuit Court!) instructed the jury, “The plaintiff had the right to take a seat where she did in the ladies’ coach, and … any attempt . . . to make her move into . . . another coach was a violation of law and of her rights.” The judge told the jury if they found that the conductor made Mrs. Lander move to another car, “The jury must find for plaintiffs the damages they have sustained.” The judge added that the jury “are not confined to actual damages, but may take into consideration the humiliation and injury to the feelings of the plaintiff.” The jury found in favor of Mrs. Lander and awarded her damages of $125 [~$4,750 in 2025]. A majority of the Kentucky Court of Appeals reversed the verdict, saying the judge’s instructions to the jury conflicted with the state’s law requiring separate coaches for White and Black passengers. Two of the judges filed separate opinions expressing their displeasure with the racial prejudice inherent in the state law.

In 1986, U.S. District Court Chief Judge Jack B. Weinstein had these courageous challenges to Plessy in mind when he heard a Rule 11 complaint in Eastway Construction Corporation. v. City of New York asking him to sanction a lawyer for making a frivolous argument. He refused to issue sanctions. When the Second Circuit Court of Appeals told him that he had to issue a sanction, Judge Weinstein took the opportunity to make a strong statement against sanctioning lawyers for their arguments.

Weinstein said that lawyers have ethical responsibilities to vigorously represent their clients, and these responsibilities require them to push the limits of Rule 11. He wrote:

Attorneys are . . . placed in a dilemma because they have the right—in fact, they have an ethical obligation . . . to present to the court all the nonfrivolous arguments that might be made on their clients’ behalf, even if only barely nonfrivolous. They are forced by their position as advocates in the legal profession to live close to the line, wherever the courts may draw it.

Weinstein added, “Sometimes there are reasons to sue even when one cannot win.” He turned to the history of challenges to “separate but equal” doctrine to make his point:

Bad court decisions must be challenged if they are to be overruled, but the early challenges are certainly hopeless. The first attorney to challenge Plessy v. Ferguson was certainly bringing a frivolous action, but his efforts and the efforts of others eventually led to Brown v. Board of Education. . . . Vital changes have been wrought by those members of the bar who have dared to challenge the received wisdom.

In 1993, Rule 11 was amended to clarify that arguments for “reversals of existing law or for creation of new law” are not “frivolous” if the litigant “has researched the issues and found some support for its theories even in minority opinions, in law review articles, or through consultation with other attorneys.” The amendment added that arguments specifically identified as calling for a change in the law are “viewed with greater tolerance.”

Legal realism points the way to investigate federal anti-Indian law.

The realm called “federal Indian law” is a world of highly malleable doctrines created by the United States to claim ownership of Native lands and dominate Native Peoples. These doctrines—originally openly based on “Christian Discovery” and openly asserting claims of a right of domination—gradually were camouflaged as “protection”, “guardianship”, or even “tribal sovereignty.”

Felix Cohen’s 1942 Handbook of Federal Indian Law occupies a special place in the history of the field. It was the first compilation of cases, statutes, treaties, and agency regulations, and it still has the status of a bible even though it has gone through many revisions.

Cohen was a legal realist. He prepared the Handbook to maximize the space for arguments in favor of Native Peoples, though admittedly within the overall framework of US claims of a right of domination. He organized precedents in such a way as to help unbind legal arguments from doctrines intended to destroy Native Peoples. To do this, he read some cases strictly and others loosely.

Cohen’s original work was displaced in 1958 shortly after his death. The Department of the Interior published a revision that was essentially a bowdlerization of the Handbook, redacting much of Cohen’s work and even inverting some of his arguments. The history of the Handbook demonstrates the force field of arguments about the doctrines defining the relationship between the United States and Native Peoples.

The twists and turns of federal anti-Indian law illustrate the indeterminacy of law. They also demonstrate that the field is ripe for being picked apart, going underneath old cases, finding ways to set them aside as historical anachronisms, binding them to their colonial past, uprooting them as controlling doctrines in the present.

In 1906, Professor Henry S. Redfield described an entrenched legal doctrine as “impregnable…an active and conquering force.” But he wrote those words as part of a project to improve law school education—more specifically, to prepare lawyers to “make war” for their clients.

The danger associated with challenging entrenched doctrine leads most litigators to avoid attacking or criticizing “Christian discovery”. The fact that doctrines of “diminished Tribal sovereignty” and “plenary federal power” may have tactical utility in a particular lawsuit further encourages a lawyer’s inclination not to rock the boat by strategic challenge to the underlying claim of a right of domination. Even some academic commentators prefer to take a safe course to avoid the taint of possible “frivolity” among their peers. But these nonactions endanger the goal of revoking “Christian discovery” and its allied doctrines.

Despite the difficulties and dangers of doctrinal critique—read, legal change—there are cases of creative, aggressive lawyering (and courageous plaintiffs and defendants) that provide examples worth studying. We may look at some of these in a later post.

The truly tragic part of it all is that, instead of a genuine search for 'justice,' our legal system diverts the efforts of everyone involved into the gobbledy-gook you so clearly describe. It reminds me of members of uncontacted tribes who sacrifice themselves - learn languages, put on 'acceptable' clothing, etc. - so they can advocate for their peoples at international forums like the UN. I can only admire both their and your perseverance.

Fascinating. I can start to make sense of a previous question I asked- if 'legal realism' traces back to Holmes, I'm guessing it is related to philosophical Pragmatism. I always felt Pragmatism, for pragmatic reasons. needed to ground itself in some conception of tradition as the collective wisdom of the species (or at least of a culture) to be coherent and not too free-floating. That did not go over well when I presented a paper defending it at the Society of American Philosophy, to say the least. I think (but could be woefully wrong) that if you mapped that over to law it would be something like a grounding in Common Law (and ultimately, Natural Law), and then interpretation adapting it to current realities (the creative aspect vs. the 'fixed' aspect) would come in. I'm guessing 'legal realists' would resist that move?