"THE LAW IS TERROR PUT INTO WORDS"

'Analysis of the Increasing Separation Between Concerns of Law and Concerns of Justice'

Originally published in Learning and the Law, vol.2, no. 3 (American Bar Association Section of Legal Education, 1975), which the editors called “our New Year's Issue” https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/latlw2&i=181

There is now a study of law that exists independent of the law school world and extends beyond those boundaries of legal education within which the training of lawyers takes place. The creation within the last half decade of degree programs in legal studies has ended the hegemony of law schools in legal education.

It is my purpose in this essay to focus on that form of legal studies which is critical, humanistic and self-developmental in its educational goals. And in this context, I will explore the potential for the emergence of a fundamental restructuring of the way we think about law.

After five years of teaching and studying law within the framework of a college curriculum, I have come to regard this mode of legal studies as a form of cultural action. The barriers and suspicions which have isolated the study of law within law school are transcended through this action, opening the way to a reexamination of basic assumptions and thought patterns underlying our traditional views of law.

A humanistic and critical approach to legal studies, emphasizing the development of self-knowledge, begins by drawing together the ways in which the phenomena of law have been studied by various scholarly disciplines. Jurisprudential, sociological, historical, economic, psychological, anthropological and other modes of analysis are brought into an interdisciplinary focus. Building on the interpenetration of different modes of thought, this approach to legal studies become transdisciplinary. The transition from interdisciplinary to transdisciplinary inquiry is extremely important. It is the necessary effect of a serious interpenetration of disciplines.

Much of the failure of “law and society” programs in law school has been due not so much to an inability to achieve cooperation across disciplinary lines as to the refusal to move beyond the notion of separate but equal discipline structures. Interdisciplinary study assumes the validity of paradigms which structure inquiry within each discipline and hopes for an expansion of knowledge by a kind of teamwork approach to a subject. The anthropologist, sociologist, economist, lawyer, and so on, are all supposed to work together, yet each is also supposed to represent a particular discrete mode of inquiry. The tension in this situation, though it may at first promise to be productive, is most likely to be resolved by the withdrawal of the disciplinarians, each to their original epistemological shelters. The situational demands of the study task succumb to the career and other demands of the separate disciplines.

The crucial quality of transdisciplinary study, on the other hand, is found in the reversal of these demands. The study task is primary, while the disparate disciplines are viewed as starting points only. Indeed, transdisciplinary exploration begins with the realization that any discipline functions as much to limit inquiry as to structure it, and then proceeds to examine the universe of questions which surround every discipline.

Legal studies, in its most significant form, involves such an exploration into the unknown.

CHANGING CONSCIOUSNESS OF LAW

We are living in a time of changing consciousness about the meaning and function of authority. Law, which is often taken to be the backbone of authority structures in society, has come increasingly under scrutiny, both for its role in maintaining oppressive social conditions and for the exceeding narrowness of legalism as a worldview.

In a sense, we no longer believe in our system of legal rules the way we used to. We are beginning to see through the facade of a “government of laws” to the people who animate that system. And further, we are coming to understand that legalism is as much an obscuring veil as a clarifying lens for approaching social problems. Law and legal thinking are as frequently the cause of social trouble as the means of resolving it. Thus, as Addison Mueller has noted, in our “free enterprise” economy, “freedom of contract” is the consumer’s losing card [“Contracts of Frustration”, 78 Yale L.J. 576 (1969)].

This growing skepticism and criticism about law is part of the decline of legalism in our culture. The decline, however, is not a simple matter. It is beset with resistance and contradiction. For example, even as the evidence becomes more and more clear that prison is a dysfunctional, self-defeating, self-perpetuating social institution, the force of the state is called again and again into action against the victims of that institution. Likewise, even though crime is increasingly understood to be a product of social stratification, rather than a phenomenon of human nature against which society structures itself, the state spends ever more money to preserve the existing social structure and to thwart the forces of social change.

In an overall way, these contradictions are forcing us to realize that our justice system is only another social institution, subject to all the ills that befall any other institution: bureaucracy, preoccupation with its own maintenance and expansion, depersonalization of those whom it is supposed to serve, etc. Disenchantment with law as the basis for authority in social and personal life is now so pervasive that we are at a crisis in the history of law itself.

The real significance of legal studies is its ability to cope with the disenchantment. It does not limit itself to a civics or government class exegesis of the basic documents of legalism. Instead, it proceeds to an analysis of the evolution and structure of the society built on those documents, together with an historical, cross-cultural and transdisciplinary investigation of the concepts and forces at work when people unite into groups.

The central purpose of law school education, on the other hand, is socialization into the legal profession. This process is the antithesis of free and open-ended inquiry into the nature and function of law. That is why the contracts teacher, for example, cannot pause to consider the basic injustice of “freedom of contract” in a monopolistic economic system. To do so would not only take time away from the job of teaching how to manipulate legal doctrine, it would positively disrupt the socialization process itself. That is, criticism of basic legal forms and processes is incompatible with the inculcation of allegiance to the framework of legalism as a way of thinking and acting.

This incompatibility is especially significant in the first year of law school. It is there that so many idealistic young people, eager to “help others” and “change society,” first encounter the full force of legalism and come to grapple with its peculiar and surprising ability to step aside from every question of substance and value conflict. Questions about social history, or economics, or psychology, or even of philosophy, are admitted into the classroom only to the extent that they do not distract from the main task. That task is learning how to sidestep all such questions in the parsing of doctrine and, thus, in the exercise of legal power.

Law students are taught to seek and use power, rather than truth. And as a way of persuading them to give up any persistent pursuit of the latter, they are encouraged to think of the “justice” they can accomplish when they have acquired power. The first year is complete when the students can no longer separate “justice” from “law,” and when all critical consciousness has been engulfed by positivism and social relativism.

A critical, humanistic legal studies program, in contrast, does not take as its starting point an acceptance of the particular form of law which has developed in this society, nor a commitment to socialize its students into such an acceptance or allegiance. Indeed, this kind of legal studies is so far removed from such an uncritical approach, that it is in fact willing to start with premises that are diametrically opposed to the structure and concepts of legalism. It is not afraid to admit that legalized oppression is a reality to many people in this country. In a legal studies class, questions about the fairness of the structure of economic activity and of the legal apparatus sustaining and enforcing that structure are not only admissible, they are central.

A discussion about criminal law would not be complete without an examination of the social history and politics of crime control. Similarly, psychological and sociological data are scrutinized for an understanding of such phenomena as oppression and social stratification. The aim of such scrutiny, furthermore, is not the inculcation of an easy social relativism, but rather the development of a critical consciousness about what might be called the “politics of everyday life.” This is an arena of activity that is not apprehended by the method or framework of legalism, due to the latter’s elevation of official explanation over personal experience.

It is interesting to note that this kind of critical approach to law study occasionally meets with resistance even among undergraduates. Business school students, for example, are more likely than others to feel threatened and annoyed by a critique of legalism. It is their very professionalization and allegiance to the ideology of capital which is shaken by such criticism. Most people do not like to have basic assumptions challenged; they fear the ambiguity which is generated in this process. But for those who are building a career on the challenged assumptions, the fear of ambiguity can be paralyzing.

I have, on occasion, asked in class, “What is the difference between business and stealing?” and “What is a loophole in law?” The response to these queries is usually laughter and a quick rush of suggested answers. As the students are pressed on their answers to the first question, and it becomes clear that no logical or philosophical explanation exists to rationalize the distinction in an overall way, the atmosphere grows more serious.

An underlying feeling of confusion sets in, and the students are ready to look deeper into the ideology of legalism and at the process of legal socialization (how people come to learn and accept legal distinctions, etc.). Similarly, with the second question, students begin to ponder the significance of a concept which has meaning only within a legalistic social structure, and yet whose function is to permit escape from the structure. That the concept has no true juridic existence is a paradox which stimulates further inquiry into the nature and function of law, its value orientation, and so on.

In this mode of legal studies, as education about law rather than education in law, one is free to see legalism itself as pathology rather than enlightenment, as a manifestation of social alienation rather than a means to social unity, as dispute-masking rather than dispute-settling, and as a handmaiden to economic exploitation rather than a mechanism for equity in resource allocation.

As professional law training is distinguished by its commitment to the existing legal system, to the ideology of legalism that informs that system, and to the social order which the system and the ideology both serve, so is a critical legal studies distinguished by its freedom from these commitments and its consequent ability to provide a basis for analysis of the very thought structures which underpin the legalistic ethos.

Law school, having excluded any external vantage point from which one might gain a critical perspective, is thus unable to comprehend the actual effects of legalism on the society in which it operates. With minor exceptions, even natural law—positivism’s only serious antagonist within the law school world—is no longer a viable option. The result is that professional legal education provides no basis for analyzing the psychic and social phenomenon of legalism, and no entry point through which any such critique might enter the curriculum. That such a critique can be built, however, is exceedingly clear.

WE ARE AUTHORITY ADDICTS

Daily life under legalism is permeated in all its aspects by a belief in authority, and an accompanying tension between authoritative descriptions of the world and our own individual perceptions of life. We are authority addicts, hooked on rules. As Judith Shklar has noted, the institutional and personal levels of commitment to legalism form a social continuum:

At one end of the scale of legalistic values and institutions stand its most highly articulate and refined expressions, the courts of law and the rules they follow; at the other end is the personal morality of all those men and women who think of goodness as obedience to the rules that properly define their duties and rights. [Legalism (1964) p. 3].

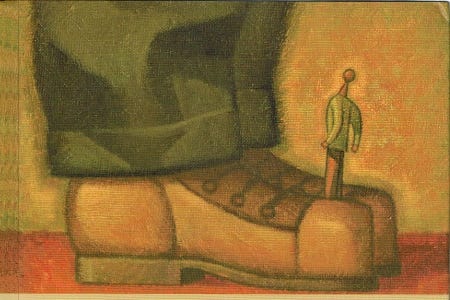

At every moment, even to the level of how and when to eat, smile, sleep, talk, touch and move, and beyond this to the level of how and what we are supposed to think, fantasy, and dream, there are rules. Life for most people seems to be a project of obedience, of duty, and responsibility to authority. Constantly there is the struggle to fit ourselves into someone else’s dream, someone else’s definition of reality. And with this struggle, as part of it and in turn perpetuating it, goes a fear of letting go of authority as well as attempts to impose our authority on others, preoccupation with what others think, feelings of isolation from others and the world, and fear that we will not exist if we do not define ourselves, label our relationships, and categorize ourselves and each other.

David Cooper, studying such phenomena in The Death of the Family (1971), writes:

If, then, we wish to find the most basic level of understanding of repression in society, we have to see it as a collectively reinforced and institutionally formalized panic about going mad, about the invasion of the outer by the inner and of the inner by the outer, about the loss of the illusion of “self.” The Law is terror put into words (p. 33).

Under legalism, we are constantly trying to control ourselves and each other within limits laid down by authority, all the time not seeing any alternative to this positivistic world, accepting it as necessary and inevitable. In law school, one learns to put the terror into words and to conceal its true nature. The heart of law school training is the refinement into positivism of a pre-existing allegiance to authority, the inchoate legalism acquired by the ordinary person in school and family.

The vaunted “case method” is nothing more than a frank recognition that authority is what counts: what is important to the lawyer is what has been held to be important.

The law student learns that finding the law regarding some particular social or economic conflict is more important than understanding the conflict. The student is trained to manipulate the language of a judge’s opinion, and to exclude etiological consideration of the decision and its rationale: social, political, historical, and other factors and forces involved in the case, and in the power structure encompassing the case. These latter concerns are at most only referred to and relegated to other “non-law” realms of inquiry.

The verbal framework and apparatus for the exercise of power which is thus created in law school becomes reality for the lawyer; the legal system takes primacy over the effects it has on real people in real social situations. Witness Edward H. Levi, discussing “The Nature of Judicial Reasoning”:

Perhaps it should be said that the effect of ... (a legal decision) so far as the judge or lawyer is concerned is primarily on the fabric of the law. The lawyer’s or the judge’s function may be sufficiently self-delimited so as to exclude from the realm of their professional competence the larger social consequences . . . For the judge or lawyer the relevant effects are upon the web of the law, the administration of law, and the respect for law [Law and Philosophy, Hook, ed., (1964) p. 264].

The result of this process, as legalism continues to build on itself, is an increasing separation between the concerns of law and the concerns of justice. Law becomes preoccupied with preserving itself and the social order with which it is identified. The concern of justice, in contrast, remains the achievement of social wholeness rather than simple order.

Charles Silberman, in his powerful critique of the 1971 AALS [Association of American Law Schools] curriculum study report, “Training for the Public Professions of the Law,” pointed out this divergence between the concern for social order and a concern for justice. Noting that the words “justice” and “injustice” do not appear in the AALS report, Silberman called for the “depoliticalization” of law school, saying that law school is:

…politicized through its commitment to the status quo. . . . The point is that where gross injustice exists, the pursuit of justice may involve the exacerbation of social conflict, not its resolution. It is precisely this commitment to conflict resolution rather than to justice that creates the lawyers bias for the status quo….

Free from the law school devotion to the ideology of legalism, the legal studies student is able to reach realms of inquiry which are only dreamed about by law school people:

[Professional] legal education faces two choices today: either (a) diversify the three years so that the student acquires the rudiments of an understanding not merely of what has hitherto been understood as “the law” but of the interrelations of social knowledge with the law or (b) reduce the minimum time-serving requirement to two years with a resulting emphasis on doctrinal analysis. The first alternative is very alluring; the trouble is that no one has been able to say in any detail how such a curriculum relates to the practice of law [New Directions in Legal Education, Packer, Ehrlich, and Pepper (1972), p. 80].

The reasons for such a narrow curriculum, however, are not as bland as the idea of relevance to practice might suggest. In fact, many parts of law school curricula have little relevance in any direct sense to actual practice of law, and many aspects of practice are almost universally ignored in law school. The more basic reason for the narrow curriculum goes to the socialization process and the importance of maintaining the legalistic worldview as overriding ideology. The long and short of it is that the broader curriculum would open the door to subversion of this ideology.

The wide-open study of law as a phenomenon of human life calls for an exploration of explanations that are not normally admitted into the law school curriculum because they are anti-legalist in nature—Marxist and anarchist views, for example. The serious study of such alternative views of the nature and function of law would disrupt the socialization process.

In legal studies, the sacred cows of legalism become fair game, as two examples may demonstrate. The concept of a person’s “rights,” for example, is basic to legalism. It is one of the most powerful formulations in gaining and sustaining popular support for the operation of the legal system.

The common understanding of this concept is that law takes the side of the people against governmental or other systematic injustice. This uncritical view is elaborated upon in law school and throughout the legal system. Actually, however, once one understands that the central concern of legalism is with the maintenance of its own power system, one sees that the law only appears to take the side of the people. In fact, the real concern of legalism in its recognition of popular claims of right (civil rights, etc.) is to preserve the basic governmental framework in which the claims arise.

The concept of civil rights has meaning only in the context of an over-arching system of legal power against which the civil rights are supposed to protect. Ending the system of power would also end the need for civil rights. But it is precisely here that one sees the impossibility of ending the oppression by means of civil rights law. In the end, this analysis points to the concept of personal “rights” as being a technique for depersonalizing people. We are taught to respect the rights of others, and in doing so we focus on the abstract bundle of rules and regulations which have been set up by judges and other officials to govern the behavior of people. In this focus, we miss the actual reality of the others as whole, real individuals. We end up, in short, respecting the law rather than people; and this, for legalism, is the essential aim.

Due process is another sacred cow become fair game. Legalism would have us regard this notion as the key to freedom under law, the means by which fairness and regularity are incorporated into legal decision-making. In reality, due process is the attempt of the system to insure that claim and counterclaim, freedom and grievance, both occur only within the existing legal universe and in its terms.

Every due process decision is thus only a further elaboration of the pre-existing legalist mazeway. People confront the claim of law to control social life, and the law responds; whatever the legal response to the confrontation, the law is concerned with itself first and foremost. The basic due process problem, as far as legalism is concerned, is only to preserve the apparatus of official legal control, even when the framework of that control must bend to meet the demands and needs of the people whose lives the officials govern. In a critical view, due process is essentially a technique for co-opting social change forces that threaten, or appear to threaten, official control of society.

In my own experience in practice—in an urban ghetto, on an Indian reservation, and in a middle-class college community—I found again and again that people were able to see through law and legal processes in ways that I had been taught to close my eyes to. When their vision was rebuffed by law, it became the basis for a deep cynicism about legal process. I saw, moreover, that even when lawyers succeeded in legalisms’ own game—the creation of a new rule, or the vindication of an old one—that we didn’t really win anything, because legalism wasn’t dealing with the roots of problems, but only with their surface appearances.

And it is only “radical” law or legal services practice which generates such insight and skepticism. I found many traditional lawyers in conventional practices who were well aware that the law was not reaching their clients’ real problems: economic, familial, psychological, and so on. These lawyers were sometimes deeply troubled by this awareness, and yet they remained unable even to articulate their experience. Locked into the mazeway of legalism in their education, and bereft of any critical viewpoint, they seemed resigned to a life of legal routine.

As my own critical consciousness has developed, I have come to regard legalism as a defunct social ideology. Capable at one time of unleashing tremendous productive social forces, legalism is now only a source of confusion and contradiction. Far from uniting America into a coherent and just society, traditional ideas of law foster division and give the stamp of approval to inequality.

ONE LEGACY OF LEGAL REALISM

If “authority” is needed for this iconoclastic view of legalism, one need only look back to the last major jurisprudential shakeup in American history, legal realism. Karl Llewellyn, one of the most profound thinkers and observers in the realist movement, commenting on “the place and treatment of concepts,” wrote [in “A Realistic Jurisprudence—The Next Step”, Columbia Law Review 453 (1930)]:

…Categories and concepts, once formulated and once they have entered into thought processes, tend to take on an appearance of solidity, reality and inherent value which has no foundation in experience.

In a time like the present, when belief in the central myths, or explanations of reality, around which our social life has been organized is increasingly breaking down, it becomes especially important to go beyond superficial exploration of social phenomena to an examination of concepts. The legal realist movement opened the door to new ways of thinking about the law, ways colored by non- or even anti-legalist perspectives.

The cry to go beyond legalism has come from other quarters, too. Brainerd Currie, writing about the materials of law study in the early and middle 1950’s put forth an unmistakable critique:

Solutions to the problems of a changing social order are not implicit in the rules and principles which are formally elaborated on the basis of past decision, to be evoked by merely logical processes; and effective legal education cannot proceed in disregard of this fact. If men are to be trained for intelligent and effective participation in legal processes, and if law schools are to perform their function of contributing through research to the improvement of law administration, the formalism which confines the understanding and criticism of law within limits fixed by history and authority must be abandoned, and every available resource of knowledge and judgment must be brought to the task [quoted in Packer, et al., New Directions in Legal Education 268 (1972)].

A humanistic legal studies accepts this challenge in a context that is wider than Currie’s concern for legal process and law administration. Dealing with the central themes of human social life in a problem-oriented, question-posing way, this mode of study is free to pick up on even the most radical and far-reaching changes which are occurring in human consciousness. Legalism’s continuous attempt to preserve old values by giving them new meaning can be replaced by an attempt to follow new meanings into a transvaluation of the central features of law and social life.

Professional legal education is an example of what Paulo Freire calls “the banking concept of education:”

Education thus becomes an act of depositing, in which the students are the depositories and the teacher is the depositor. Instead of communicating, the teacher issues communiques and makes deposits which the students patiently receive, memorize, and repeat. This is the “banking” concept of education, in which the scope of action allowed to the students extends only as far as receiving, filing, and storing the deposits. They do, it is true, have the opportunity to become collectors or cataloguers of the things they store [Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1974) p. 58].

At first, the law teacher “owns” the law and the students seek to possess this as a piece of property, something worth having. Later, the property having been conveyed, the students enter into the status of co-owners, taking upon themselves the role of guardian of this property which they have acquired and which will support them as a means of earning a living. The fact that all this takes place under the name of the “Socratic method” with its apparently vigorous student-teacher interaction only serves to mask the banking-concept implicit in the socialization process of legal training. As Paul Savoy has pointed out, the so-called Socratic method is actually only the “degradation ceremony” attendant to the law school socialization process [“Toward A New Politics of Legal Education,” 79 Yale Law Journal 457, 468 (1970)].

In legal studies, on the other hand, at least in its humanistic, self-developmental mode, the teacher is a student among students. Students and teachers are engaged as partners in critical thinking and a mutual quest for humanization. In this quest, the existing cultural framework of legalism is viewed not as a limit but as a challenge in an ontological and historical process of people becoming more fully human.

There is no reason why law schools cannot follow this path. Indeed, every first-year class presents an opportunity to cool out the socializing process, to widen the scope of discussion, to foster a critical awareness of law. If only the question, “What is justice?” were admitted, and the concrete study of injustices were permitted, law schools might become places of creative work. Students and teachers might move from the nearly exclusive focus on litigation and doctrine to an exploration of other modes of social conflict resolution. They might explore more creative ways of approaching the legislative and executive functions of government. They might pay more attention to political process, including both the formal system and also an exploration of community and group processes. All of these things are possible. What will be necessary, however, in order for movement in this direction to occur, is the emergence of a radical consciousness, an awareness of life that goes beyond positivism and social relativism. And this means that the inadequacy of legalism must be admitted.

Legalism is no longer the ideology of human freedom and liberation. It is the ideology of the state and of property. When the law schools can go this far, their classrooms will become experimental laboratories in self-government, offering to the world both a new vision of human freedom and concrete proposals for social transformation.

In legal studies, our search is for a way of life and a paradigm for understanding law which do not require the acceptance of social oppression and personal repression as unalterable features of human existence. It is a search which is a praxis: reflection is merged with activity so that we are neither academics separated from the “real” world, nor “activists” cut off from the process of inquiry and education.

A transcending paradigm is not merely an idea to be imposed upon the thinking and behavior of people. It is a worldview which arises from the conscious living of people, out of our common struggle to understand and intervene in the processes by which human reality is created. Education on this scale is the objective of critical, humanistic, self-developmental legal studies.

In 1977, two years after my article, Grant Gilmore wrote The Ages of American Law, where he said:

Law reflects, but in no sense determines the moral worth of a society. . . . The better the society, the less law there will be. In Heaven, there will be no law, and the lion will lie down with the lamb. . . . The worse the society, the more law there will be. In Hell, there will be nothing but law, and due process will be meticulously observed.

Here’s what the editors said about the ‘New Year’s issue:

NOTE FROM THE EDITORS - https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/latlw2&i=143

AN EYE TO THE FUTURE

This might be called our "New Year's Issue" of LEARNING AND THE LAW. Not only is it the last number of the magazine to appear in 1975, but, more importantly, many of the articles presented here embody the spirit of this time of year. It is a spirit of reassessment, of looking backward and ahead, of evaluating the past and setting goals for the future. …

Some of LEARNING'S readers may be surprised at the extent to which Peter d'Errico, in another article included here, seeks to break away from common modes of thought about legal education. But his paean to the virtues of legal studies programs cannot be ignored. Indeed, some scholars would say it is the voice of the future calling the past to an accounting. …

We are pleased to have you join in this look toward the future. And we wish you a happy new year. -The Editors

My only critique of the critique is that so often the formulation of the antongists to the establishment in the form communism or libertarianism or anarchy are fundamentally anti-God not in the sense of seeing past idols including those of empire and imperialism and legalism but in terms of serving cult interests that are dark in their inverted distortions, often guised as atheism but actually serving the inverted religion that is the opposite of love.