"Political Principles and Indian Sovereignty": Lee Hester's Philosophical Critique of US Anti-Indian Law

How does a 15th century religious doctrine survive in a legal system that supposedly separates religion and law?

IN THIS POST: “Christian discovery” contradicts the supposedly secular nature of the United States. Lee Hester says: “We cannot seriously consent to a law that would allow countries to ‘legitimately’ take over other countries just because they are the ‘wrong’ religion.”

Professor Lee Hester is a citizen of the Choctaw Nation, Director of American Indian Studies at the University of Science and Arts of Oklahoma, and one of the leading Native American philosophers in North America.

In 2001, Hester published Political Principles and Indian Sovereignty.

He took aim at the divergence between professed values of the US and realities of its laws related to Original Nations and Peoples — so-called “federal Indian law”. Like me, he understands that it is really federal anti-Indian law.

Hester is a philosopher who can write to be understood outside the academic world of philosophy. He focuses on moral claims made by US leaders like George Washington, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson, who mouthed words of “sympathy for the Indians” while building an empire of domination over them.

US Anti-Indian Law: “Sympathy” and Domination

The trope of “sympathy” accompanied by domination is common in federal anti-Indian law. It has a long pedigree, going back to one of the three cases that established the field, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831).

In Cherokee Nation, Chief Justice John Marshall said:

“If Courts were permitted to indulge their sympathies, a case better calculated to excite them can scarcely be imagined.”

Marshall dismissed the Cherokee case, washing his sympathetic hands of any stain:

“If it be true that wrongs have been inflicted, and that still greater are to be apprehended, this is not the tribunal which can redress the past or prevent the future.”

Hester knows that most people pay no attention to philosophy, so it is no surprise that they miss these inflection points in the dominant narrative:

“Do American philosophers exert influence? … Certainly as far as the wider society is concerned it must be said that the answer is emphatically negative. …

“In so far as they exert an external influence at all, it is confined to the academics of other fields.”

Lawyers and judges generally avoid philosophy as “impractical” in litigation. And even academics often miss the inflection points where philosophy intersects with action. They therefore are often taken in by Marshall’s philosophical “sympathy” for Original Nations and Peoples — as if that takes the sting out of the Cherokee Nation declaration of US domination over them:

“The tribes …[cannot] be denominated foreign nations. They may more correctly, perhaps, be denominated domestic dependent nations.”

Marshall coined a phrase that quickly became controlling legal dogma:

“Their relations to the United States resemble that of a ward to his guardian. They look to our Government for protection, rely upon its kindness and its power, appeal to it for relief to their wants, and address the President as their Great Father.”

As Hester puts it:

“The ‘guardianship’ of the United States over Native Americans constituted an extension of power over them. …

“By claiming ‘guardianship,’ [the US] assumed preeminence and control.

Marshall said the basis of the Cherokee Nation decision was the claim of US “ownership” of Original Peoples’ lands:

“The Indians… occupy a territory to which we assert a title independent of their will.”

The claim of US “title” to Original Peoples’ lands is the doctrine of “Christian discovery”, which the Supreme Court adopted in Johnson v. McIntosh (1823), the first of the three cases that established federal anti-Indian law by creating a rule of US property law.

The Johnson decision said:

“The English [acquisition of] territory on this continent [was based on] the right of discovery [of] countries then unknown to all Christian people. [emphasis in original]”

“…notwithstanding the occupancy of the natives, who were heathens, and… admitting the prior title of any Christian people who may have made a previous discovery.”

“The United States…have unequivocally acceded to that …rule….”

To rub salt into the wound, Marshall described the decision as an “extravagant . . . pretension of converting the discovery of an inhabited country into conquest.”

Marshall’s metaphor of “dependency” continues to dominate the quasi-philosophical framework of federal anti-Indian law in updated lingo:

“Ward/guardian” is now “trust relationship”.

“Domestic dependent nation” is now “government-to- government relation.”

As late as the mid-20th century, the US was not ashamed to speak openly about “Christian discovery”.

In the case of Tee-Hit-Ton v. United States (1955), the US Department of Justice told the Supreme Court:

“The Christian nations of Europe acquired jurisdiction over newly discovered lands by virtue of grants from the Popes, who claimed the power to grant to Christian monarchs the right to acquire territory in the possession of heathens and infidels.”

The DOJ admitted that some people thought this was an injustice and a violation of Original Peoples’ rights. It said:

“Principles of natural law, and abstract justice, are appealed to by some, to show that the Indian tribes . . . ought . . . to be regarded as the owners of the . . . soil they occupy.”

But the DOJ rejected those arguments:

“The fundamental principle, that the Indians had no rights, … either of soil or sovereignty, has never been abandoned.”

The DOJ cited Johnson v. McIntosh and told the court that the US government had succeeded to the claims of colonial Christian monarchs:

“Thus, it is abundantly clear that the sovereign's ownership of the lands on this continent came, not from any grants by the native Indians, but rather from the principle of discovery.

“And it is likewise plain that the Indians retained only a right of occupancy through the grace of the sovereign.”

The brief persuaded the court to rule against the Tee-Hit-Ton. Justice Stanley F. Reed wrote the majority opinion. He said:

“It is well settled that…the tribes who inhabited the lands of the [country] held claim to such lands after the coming of the white man, under what is sometimes termed original Indian title or permission from the whites to occupy.”

Reed sidestepped the US brief’s citation of Christian religion, but he did cite “the great case of Johnson v. McIntosh” and said:

“This position of the Indian has long been rationalized by the legal theory that discovery and conquest gave the conquerors sovereignty over and ownership of the lands thus obtained.”

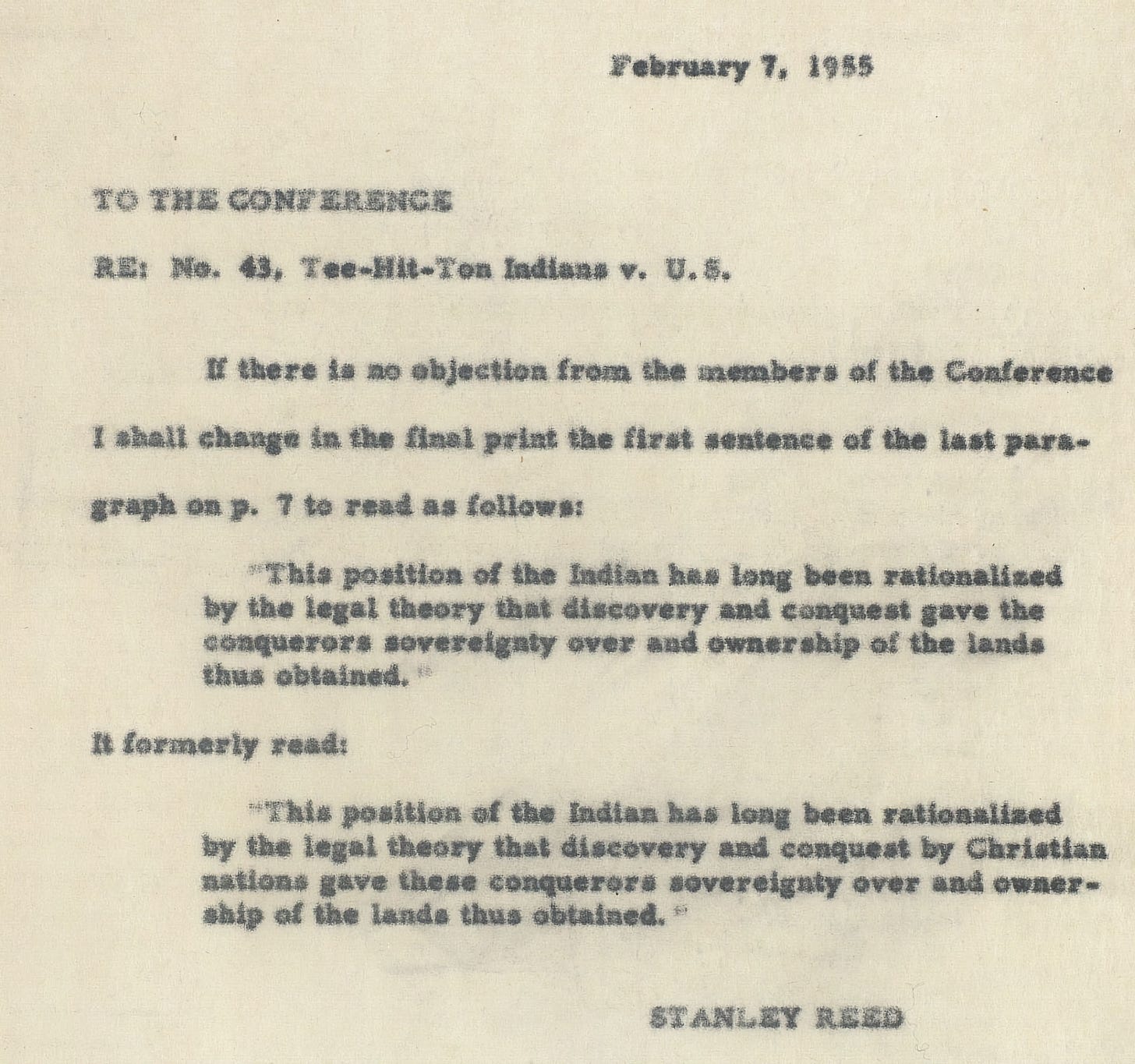

The justices grappled with the wording of this sentence up to the last minute. In drafts circulated prior to the final opinion, the sentence read:

“This position of the Indian has long been rationalized by the legal theory that discovery and conquest by Christian nations gave the conquerors sovereignty over and ownership of the lands thus obtained.”

Justice Reed deleted “Christian nations” in a memo to the court that shows the clear intention to conceal the religious grounds of the decision:

The memo was dated February 7, 1955, the same day the Court’s opinion was issued.

The Supreme Court now avoids naming the doctrine, as if that makes the problem go away.

Hester says this attempted disappearing act isn’t working. The philosophical contradictions are intensifying as the political / economic crunch intensifies between the US and Original Nations and Peoples [Think: Standing Rock, Oak Flat, Thacker Pass, Navajo water, etc.].

Hester says:

“The …colonial nations have become trapped….

“As they have come to understand how their…actions conflict with their own sense of justice, they have called into question their own right to exist.”

Hester says:

“The [current doctrine] of ‘inherent and retained sovereignty’ of the Indian nations must be seen in this light. The US is attempting to reconcile its right to exist with its own recognition of the injustices that gave it birth and nurtured it.

“The centrality of popular sovereignty to United States’ law makes it impossible not to recognize the sovereignty of Indian nations.”

But he is quick to point out:

“However, to retain its own sovereignty…the United States has subordinated Indian sovereignty under plenary power doctrine….

“The doctrine of inherent and retained sovereignty under the plenary power of Congress is just the most recent turn in the labyrinth [of federal anti-Indian law].

“The labyrinth of Indian law is necessary to hide the fact that the United States is violating its most fundamental principles… [as stated in the Declaration of Independence]”:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

Hester says that “Christian discovery” contradicts these principles and the supposedly secular nature of the United States:

“We cannot seriously consent to a law that would allow countries to ‘legitimately’ take over other countries just because they are the ‘wrong’ religion.

Hester concludes that the labyrinth of “inherent and retained sovereignty under plenary power” obscures without resolving the fundamental and deepening issue: “Either Indians are or are not a part of the United States.”

The question is becoming increasingly difficult to answer.

Only one member of the current US Supreme Court has called for a resolution of this issue: Justice Clarence Thomas:

In US v. Lara (2004), Thomas said:

“In my view, the tribes either are or are not separate sovereigns, and our federal Indian law cases untenably hold both positions simultaneously.”

“Federal Indian policy is, to say the least, schizophrenic. And this confusion continues to infuse federal Indian law and our cases.

“[The United States] cannot simultaneously claim power to regulate virtually every aspect of the tribes through . . . legislation and also maintain that the tribes possess anything resembling ‘sovereignty.’”

In US v. Bryant (2016), Thomas said:

“[US Supreme Court precedents] have made it all but impossible to understand the ultimate source of each tribe’s sovereignty and whether it endures.

“Congress’ purported plenary power over Indian tribes rests on even shakier foundations. No enumerated power . . . [in the Constitution] gives Congress such sweeping authority.”

He added that if these confusions remain, US law …

“…will continue to be based on the paternalistic theory that Congress must assume all-encompassing control over the ‘remnants of a race’ for its own good.”

Surprisingly, Justice Thomas’s critique echos Standing Rock Sioux historian Vine Deloria, Jr.’s 1971 description of federal anti-Indian law in his book Of Utmost Good Faith.

Deloria wrote:

“Using a number of illogical and irreconcilable theories of ward-dependent nation, plenary powers of Congress, and treaty abrogation the court skips along spinning off inconsistencies like a new sun exploding comets as it tips its way out of the dawn of creation.”

It remains to be seen whether Justice Thomas or any other justice will confront Christian discovery doctrine head-on and follow a demolition of federal anti-Indian law to its logical conclusion: termination of the exception that denies Original Peoples’ land ownership and full self-determination.

At a minimum, Thomas’s voice is the clearest signal, at the highest level, that federal anti-Indian law is in a state of crisis.

It is getting increasingly hard to avoid deep philosophical discussion about federal anti-Indian law that would reveal the roots of the crisis.

Contradictions are increasingly apparent.

Moreover, because federal anti-Indian law is entwined with US property law, the doctrinal crisis spirals into a deep anxiety about US sovereignty.

Lee Hester was a founding editor of Ayaangwaamizin: International Journal of Indigenous Philosophy, published by Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario (1997-2003).

As the Journal explains, Ayaangwaamizin is Anishnabe, usually translated as "to go carefully", "to tread carefully":

But beyond this superficial meaning is the idea that the actions of persons have consequences for a larger whole. The term is used in a context that assumes the meaningfulness of existence and action — we do not live in a "neutral" universe that exists beyond and outside ourselves. We are a part of the fabric of the universe.

Good to learn that the schizophrenia is being challenged. For a while i noticed the schizophrenia baked into the US consciousness, thus rather amazing to me to learn of Justice Thomas identifying as such. Walt Whitman, considered the father of free verse and one of America's most influential poets, was a populist imperialist, as he championed the common people and was one of the few to even mention Natives, yet he touted the so-called New World. Another schizophrenic example is Thomas Jefferson's "empire of liberty."

Lee Hester’s work is both philosophical and rigorously factual. Both he and Peter d’Errico touch on the question of the possible reach and influence of such work. So did John Maynard Keynes. As Keynes’ view is somewhat different, I thought that I would share it: “At the present moment people are unusually expectant of a more fundamental diagnosis; more particularly ready to receive it; eager to try it out, if it should be even plausible. But apart from this contemporary mood, the ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back. I am sure that the power of vested interests is vastly exaggerated compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas. Not, indeed, immediately, but after a certain interval; for in the field of economic and political philosophy there are not many who are influenced by new theories after they are twenty-five or thirty years of age, so that the ideas which civil servants and politicians and even agitators apply to current events are not likely to be the newest. But, soon or late, it is ideas, not vested interests, which are dangerous for good or evil.”