Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Accepts Onondaga Nation and Haudenosaunee Confederation Land Rights Case Against the US

Commission rejects US federal anti-Indian law position

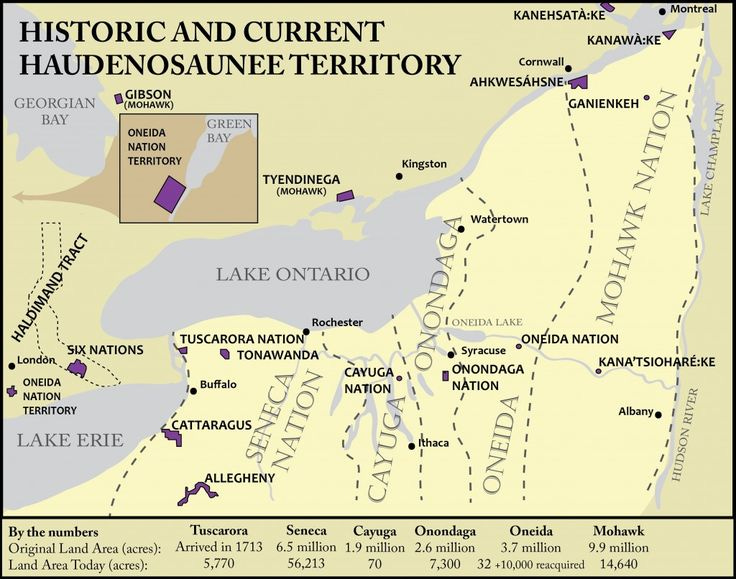

On May 12, 2023, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), an arm of the Organization of American States (OAS), issued an “Admissibility Report” upholding the Onondaga Nation’s right to pursue its claims against the United States for wrongful appropriation of Onondaga land that reduced their homelands from 2.5 million acres to 7,500 acres.

The Commission rejected the US argument that Supreme Court decisions barred the Onondaga from bringing the case. It notified US Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken on June 26, 2023, that the Onondaga Petition (No. 624-14) has been registered as a formal Case (No. 15.250).

The next step is for the Onondaga and the US to indicate whether they are interested in pursuing a “friendly settlement” instead of letting the case go to the Merits stage where the IACHR makes a decision. The Commission’s letter to Secretary Blinken requested that the US “respond to this … as soon as possible”.

Onondaga Nation General Counsel Joe Heath remarked to me in an email:

“The Onondaga filed this Petition in April 2014. The US only replied in August 2022. So it’s taken 9 years and 2 months just to reach this threshold level.”

He later said to a reporter:

“Nonetheless, this is a significant achievement for the Nation’s 235-year struggle to regain their land.”

THE REJECTED US POSITION

The US does not dispute the history of the Onondaga lands controversy.

Instead, the US told the Commission that the United States Supreme Court case of City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation ruled that “the long passage of time and settled expectations of those currently in possession …preclude …return of sovereign [Haudenosaunee] sovereignty over the Tribe’s historic lands”.

🐻 Bear with me as we look at the US argument in the federal anti-Indian law hall of mirrors 🪞🪞.

City of Sherrill was the 2005 case where Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg relied on ‘Christian discovery’ doctrine to claim US ownership of all Indigenous lands across the continent, including the Haudenosaunee.

She wrote for the court:

“Under the ‘doctrine of discovery,’ . . . fee title to the lands occupied by Indians when the colonists arrived became vested in the sovereign—first the discovering European nation and later the original States and the United States.”

This ‘doctrine of discovery’ was put into US property law by the Supreme Court in Johnson v. McIntosh (1823), where it was rationalized as a “Christian” right of domination over Indigenous peoples and lands.

Chief Justice John Marshall referred to it as an “extravagant pretension” and said:

“However extravagant the pretension of converting the discovery of an inhabited country into conquest may appear; … if the property of the great mass of the community originates in it, it becomes the law of the land, and cannot be questioned.”

Now, it’s a strange thing that US property law is based on an “extravagant pretension”. Stranger still to say it “cannot be questioned” because a lot of people took advantage of the pretense.

The Sherrill case simply repeated the pretension —the “doctrine of discovery” — and the refusal of any question. Justice Ginsburg said:

“It is impossible ... to … restore the Indians to their former rights because the lands have been opened to settlement and large portions of them are now in the possession of innumerable innocent purchasers….”

Innocence in the course of empire…. But the court is not innocent.

Reminds me of Lady MacBeth: “What need we fear who knows it, when none can call our power to account?”

The Onondaga ran into City of Sherrill when they tried to resolve this case in federal court.

The district court dismissed the case, saying:

“The Nation's claims represent the type of inherently disruptive action which …is barred under Sherrill' s formulation of a laches defense….[which applies] to any ancient land claims that are disruptive of significant and justified societal expectations….”

“Laches” in ordinary law means “unreasonable or unexcused delay…in making a claim or moving for the enforcement of a right”.

How did this ordinary definition get transformed into “disruptive ancient land claims” for federal anti-Indian law?

The judge unpacked Sherrill’s transformation formula when he dismissed the suit. He said:

“Sherrill …signaled [that] the term ‘laches’ serves as convenient shorthand…rather than a true laches defense…. It does not focus on the elements of traditional laches but rather more generally on the length of time at issue between an historical injustice and the present day….”

The judge then concluded:

“In determining whether Sherrill's formulation of ‘laches’ may bar … [an Indian land claim], courts do not need to find an unreasonable lack of diligence by that plaintiff….

“Under the principles of Sherrill… disruptiveness is inherent in the claim itself….”

The court rubbed salt into the wound caused by the twisted definition of laches:

“That the delay [in]… the Onondagas' action …may not be attributed to the Nation but to outside forces, including the actions of federal and state authorities, does not deter the Sherrill laches defense….”

The Onondaga appealed the dismissal to the Circuit Court of Appeals and offered to prove that they had not “unreasonably delayed” [i.e., ordinary laches] protesting invasions of their ancestral lands.

In 2012, the appeals court affirmed the dismissal and said:

“Even if the Onondaga showed …that they had strongly and persistently protested, the standards of federal Indian law … stemming from Sherrill …would nonetheless bar their claim.”

In short, Sherrill created its own special definition of “laches” to block ancient Indigenous land rights from being asserted in the present day, no matter how long and vigorously the rights have been asserted.

This new special for Indigenous peoples only “laches” is an example of federal anti-Indian law in action.

After the Circuit Court affirmed the dismissal, the Onondaga asked the Supreme Court to review the case. In 2013, it refused to do so.

That’s when they decided to Petition the Inter-American Commission.

Tadodaho Chief Sid Hill of the Onondaga Nation Council stated the Onondaga understanding of the age of the land dispute this way:

“The passage of time does not diminish our determination to protect our people and regain our land which has sustained us for millennia. Our view of life is linked to the core belief we must act to honor those seven generations in the past, and serve those seven generations into the future. In this case, justice has certainly been delayed. We hope it will not be denied.”

HOW THE COMMISSION RESPONDED TO THE US

The IACHR said the OAS American Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Man gives the Onondaga standing to challenge the US despite the passage of time and potential to disrupt non-Indigenous residents on those lands.

The Commission said:

“Where property and user rights of indigenous peoples arise from rights existing prior to the creation of a state, [international legal principles include] recognition by that state of the permanent and inalienable title of indigenous peoples…and to have such title changed only by mutual consent between the state and respective indigenous peoples…. This also implies the right to fair compensation in the event that such property and user rights are irrevocably lost.”

It added:

“The Inter-American Court has established that indigenous peoples who have lost total or partial possession of their territories preserve their property rights over such territories, and a preferential right to recover them even when they are in the hands of third parties. The Court has also pointed out that when a State is unable, on objective and reasonable grounds, to adopt measures aimed at returning traditional lands, it must surrender alternative lands of equal extension and quality, which will be chosen by agreement with the members of the indigenous peoples, according to their own consultation and decision procedures.”

The IACHR neatly turned the US argument about Sherrill into a ground for its own jurisdiction. It said the Onondaga tried to use the US legal system and ‘exhausted’ the possibility of getting relief from those courts:

“The Commission concludes that the decision by the US Supreme Court [refusing to hear the Onondaga case] represents the exhaustion of domestic remedies. Therefore, the current petition, received on April 14, 2014, complies with …the Rules of Procedure.”

“Based on the above, the Commission will admit the petition based on Articles II (equality before the law) and XVIII (right to fair trial/judicial protection) of the American Declaration.”

Onondaga general counsel Joe Heath told Central Current News:

“Until we get Johnson v. McIntosh and Sherrill reversed, we can’t get back into the U.S. courts.”

“There’s a strong record of human rights decisions in favor of Indigenous peoples within the Organization of American States…. It’s …a commission, not a court… which would issue a binding decision, but it is an important human rights body.”