Day of Mourning vs. Thanksgiving

Larry Mann’s novel, The Mourning Road to Thanksgiving, jumps off from Frank James’ groundbreaking speech…

IN THIS POST: The “National Day of Mourning” and the US “Native American Heritage Month” — competing perspectives on Indigenous - Colonizer relations…

Origin of the Day of Mourning - An Unwelcome Speech

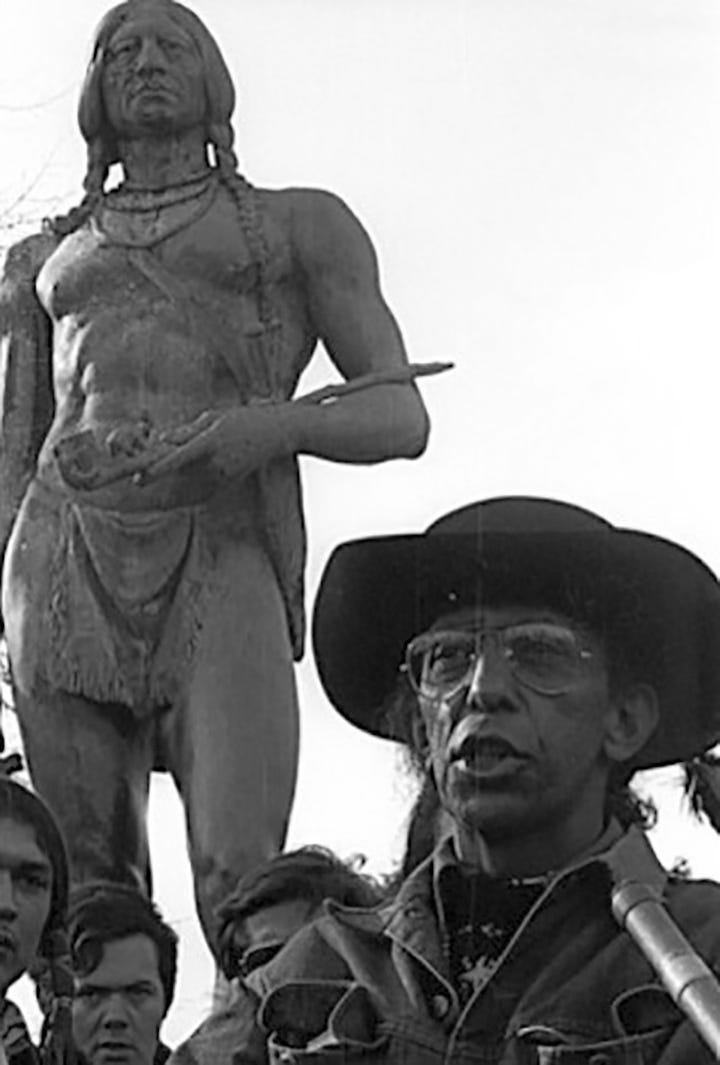

In September 1970, Plymouth, MA, planners asked Wamsutta Frank James (Aquinnah Wampanoag) to deliver a speech for the 350th anniversary of the Pilgrim invasion of (they called it an ‘arrival’ on) Wampanoag lands.

James agreed. But when the planners saw the text of his speech they refused to let him deliver it. They suggested he use a text prepared by their public relations staff. He refused.

Instead, James delivered his speech at a separate gathering, which marked the beginning of a tradition that continues to this day: The National Day of Mourning.

Since 1970, Indigenous people & allies have gathered at noon on Cole's Hill in Plymouth, Massachusetts, to commemorate the National Day of Mourning on the US Thanksgiving holiday.

The organizers say:

Thanksgiving Day is a reminder of the genocide of millions of Native people, the theft of Native lands and the erasure of Native cultures.

Participants in National Day of Mourning honor Indigenous ancestors and Native resilience.

It is a day of remembrance and spiritual connection, as well as a protest against the racism and oppression that Indigenous people continue to experience worldwide.

The First Thanksgiving - Fiction and Fact

The conventional, heart-warming story of Thanksgiving tells of a 1621 event, when a small group of Pilgrims celebrating survival of their first year were encountered by some Wampanoag men, who brought and shared food.

But the first planned, official Thanksgiving was 16 years later, when Plymouth Colony leader William Bradford designated “a day of thanksgiving kept in all the churches for our victories against the Pequots”.

The “victory” was the Pequot massacre, destruction by fire of the Pequots' major village, in which at least 400 were burned to death.

Here are Bradford’s own words, from his history "Of Plimoth Plantation”:

Those that scaped the fire were slaine with the sword; some hewed to peeces, other rune throw with their repaiers, so as they were quickly dispatched, and very few escaped. It was conceived they thus destroyed about 400, at this time. It was a fearful sight to see them thus frying in the fyer, and the streams of blood quenching the same, and horrible was the stinck and sente there of; but the victory seemed a sweete sacrifice, and they gave the prayers thereof to God, who had wrought so wonderfully for them, thus to inclose their enemies in their hands, and give them so speedy a victory over so proud and insulting an enemy.

In short, the history of the original Thanksgiving is a horror story.

National Days of Thanksgiving

Various national “Thanksgiving” celebrations have been declared in American history, starting with the Continental Congress during the American Revolution. In 1789, George Washington proclaimed a Thanksgiving to celebrate ratification of the Constitution.

In October 1863, during the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln designated a “day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens,” beseeching “the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation.”

Less than a year earlier, December 26, 1862, thirty-eight Dakota men were hanged in Mankato, Minnesota, in the largest mass execution in US history–on orders of President Abraham Lincoln. Their crime: killing 490 white settlers, including women and children, in the so-called “Santee Sioux uprising” the previous August.

National Thanksgiving Morphs into Native American Heritage Month

“Native American Heritage Month” started on August 3, 1990, when the US Congress passed a Joint Resolution authorizing the president to designate November in that way. A chain of similar resolutions and presidential proclamations have followed, up to the present.

The 1990 Resolution is notable for some bizarre language in its second “Whereas” clause:

“Whereas American Indians have made an essential and unique contribution to our Nation, not the least of which is the contribution of most of the land which now comprises these United States….”

🤯 “Contribution” of their lands!

I don’t know whether to laugh or cry. Whitewashing history while supposedly celebrating it.

The 1991 Joint Resolution deleted this clause entirely, and added a new “Whereas”:

“Whereas it is fitting that American Indians be recognized for their individual contributions to American society…as “artists, sculptors, musicians, authors, poets, artisans, scientists and scholars”.

No mention of how the US acquired its land claims.

But there was a significant change in the other direction with a rewording of the opening “Whereas”:

1990: “Whereas American Indians were the original inhabitants of the lands that now constitute the United States of America”…

1991: “Whereas American Indians are the original inhabitants of the lands that now constitute the United States of America”…

You don’t need to be a grammarian to understand that the difference between past and present verb tense carries enormous implications.

But the Joint Resolutions cut off the implications of continuing Indigenous existence by using the word “inhabitants” rather than “Peoples”.

Proclamations of “Native American Heritage Month” are designed to erase the original free existence of Indigenous nations and peoples and replace it with membership in American society.

For example:

The history of wars of extermination is laundered and turned inside-out in the 1991 clause:

“Whereas American Indian people have served with valor in all wars since the Revolutionary War to the War in the Persian Gulf….”

The history of violent colonialism is masked in the 1990 clause:

“Whereas the people of the United States should be reminded of the assistance given to the early European visitors to North America by the ancestors of today's American Indians….”

The history of George Washington as Conotocarious, or "Town Destroyer” of the Iroquois is erased by the 1990 clause:

"Whereas the people and Government of the United States should be reminded of the …support the original inhabitants provided to George Washington and his troops during the winter of 1777-1778, which they spent in Valley Forge.”

The name Conotocarious—”Town Destroyer” had its origins in 1779, when Washington ordered what at the time was the largest-ever campaign against Indigenous peoples.

Washington authorized the "total destruction and devastation" of Iroquois settlements so "that country may not merely be overrun but destroyed.”

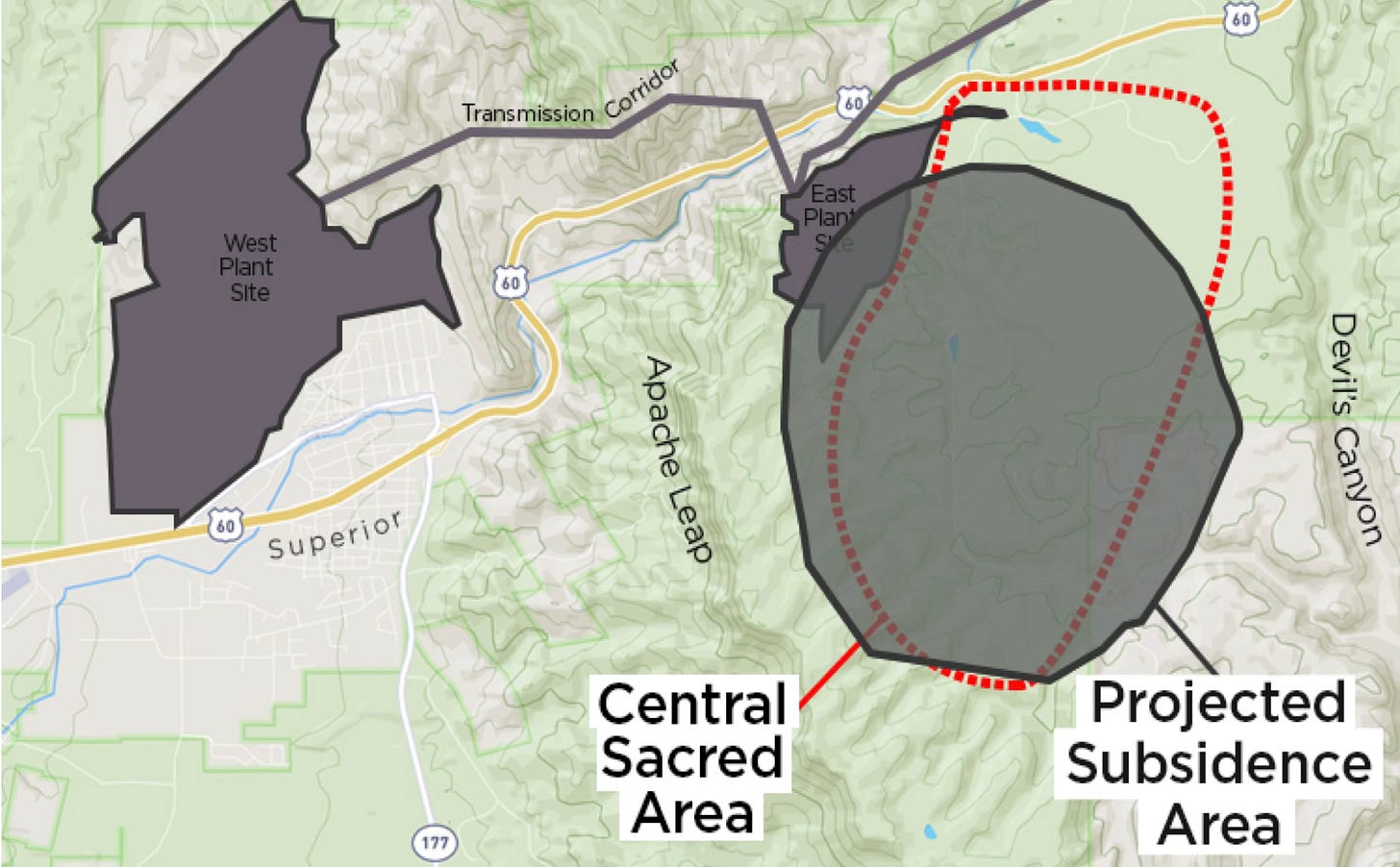

Last, but not least, we have the specially disingenuous 2023 presidential proclamation by President Biden, which flies straight into the face of his support for a copper mine on Apache land (Oak Flat) and a lithium mine on Paiute and Western Shoshone lands (Thacker Pass).

Biden said:

“We are also committed to partnering with Tribal Nations to protect and steward their sacred and ancestral lands and waters. Through Tribal co-stewardship agreements, we work directly with Tribal Nations to make decisions about how to manage those lands that are most precious to them — recognizing and utilizing the invaluable knowledge they have from countless generations.”

The Apache tell a different story:

Likewise the Paiute and Western Shoshone:

You don’t need to be a lawyer to understand that drafting a congressional joint resolution or a presidential proclamation is a fraught process.

In relation to federal anti-Indian law, which is aimed at entrapping Indigenous peoples in the name of “recognizing” them, the drafting process becomes schizophrenic.

My book, Federal Anti-Indian Law: The Legal Entrapment of Indigenous Peoples (Praeger, 2022) exposes and explores the whole framework of legalized domination.

Teaching the History… or Effacing it With Identity Politics?

You can imagine the burden placed on an American school teacher faced with teaching about this topic. A resolute engagement with the record is, to say the least, daunting in an elementary classroom.

The Library of Congress “Teacher’s Guide” says for the history of the “boarding school” system—designed to “kill the Indian and save the man”:

“This is a challenging subject to teach.”

One lesson plan suggests that:

“…students investigate an individual or group of individuals who participated in Native American boarding schools.”

🤯 Another ‘don’t know whether to laugh or cry’!

As if “participate” is an accurate verb for what the site describes as:

“Native American boarding schools…transported children far from their families, forced them to cut their hair, and punished them for using non-English names and languages. Most were run with military-like schedules and discipline….”

A Novel to Challenge the Narrative

Larry Spotted Crow Mann’s (Nipmuc) 2014 novel, The Mourning Road to Thanksgiving, offers a good grasp of the Day of Mourning vs. Thanksgiving. It is an engaging tale that engages with history.

Mann’s story centers on the experiences of a forty-year old Nipmuc man coming to terms with his life experiences in the midst of family and societal crosscurrents.

The Mourning Road works through the tropes of “Indian” identity politics. The story evokes memories of struggle, leavened with humor and laughter, as it moves toward a personal resolution of cultural contradictions built into the notion of Thanksgiving in America.

The narrative begins with the protagonist, Neempau, returning home after a decade or more away. Neempau has been radicalized not only by his experiences of anti-Indigenous hatred starting in grade school, but by his involvement with the National Day of Mourning movement begun in the 1970s by United American Indians of New England.

Neempau wants to put an end to the Thanksgiving holiday. His sister, Keenah, however, has made her peace with the dominant Anglo culture, though she clearly remembers their parents as Native activists.

The relationships among Neempau, his sister, her Nipmuc husband, who has a successful job with an insurance company, their two children, and other members of the Nipmuc community provide the framework to work through layers of confusion and contradiction in American and Indigenous cultures.

The Mourning Road to Thanksgiving deserves a special place among the resources available for people trying to learn what makes Thanksgiving a contested holiday.

Mann’s protagonist touches all the atrocities that a sensitive and critical Indigenous person cannot forget as he comes face-to-face with yet another Thanksgiving, struggling through his anger and memories, and coming to understand that "every day is Thanksgiving, so we don't need any special time or day."

Needless to say, a "special place on the calendar" does not substitute for historical dispossession and domination of Indigenous peoples.

This post is adapted from “The Mourning Road to Thanksgiving: A New Novel, an Old History”, published in Indian Country Today, October 1, 2014.

It’s happening in Hawaii, too, after the first colonizing. Wealthy transplants and some criminal workers in government has created a way too high cost of living. Native Hawaiians forced to leave the homeland. After centuries of loving care to the aina, the ocean and things of natural beauty, by Native Hawaiians, they are forced to have to leave. Entitled Newcomers not respectful of Aloha and culture are desecrating the natural wonders in Hawaii. Useful idiots, Maga flocking here to fight our way of life in support of their wealthy benefactors.

love it